“I have something on my mind. It’s a tumor.”

Joy roared with laughter even as tears streamed down her cheeks.

“That’s how Heather told all of our friends!”

Despite the tears and the choked, breathy softness that took over Joy’s voice throughout the course of our conversation, there was unmistakable pride in how she talked about Heather.

“I didn’t mourn her at all before she was gone. She believed she wasn’t going to die, so I believed it, and that was it.”

Joy suddenly seemed very far away, her smile hinting at a piece of a memory she chose not to say out loud. Whatever it was, it was just between her and Heather.

You might remember Joy Nash from one of her many theater or film roles. Often cast as a bold, brazen (and sometimes bizarre) beauty, Joy first caught the public eye with her YouTube video, A Fat Rant. Most recently she was in the latest season of Twin Peaks where she played the mysterious Señorita Dido.

And while Joy has made a career thus far on playing daring, larger-than-life characters, talking with me via Skype from her studio apartment, her three-legged cat Birthday 2 (yes, there was a Birthday 1 and he had four legs) thumping around in the background, Joy was hushed, thoughtful, vulnerable.

Every time I gave her an out, when talking about Heather just seemed too hard, she shook her head and said, “No, no, I love it, I love talking about her.”

Growing up in Redlands, California, Joy and Heather had met in the 5th grade, but were “super friends” since the 8th grade.

“We met at a tiny Christian school where there were 17 people in our 9th grade graduating class. We went to the high school the next year and there were 3000 kids, so it was huge. But we had each other.

We took most of our classes together because we were the Christians in this big, new, scary school. But we were the arty ones of the Christian kids,” Joy found this statement funny. “We were the ones in drama. We had everything in common.”

One time Heather and Joy skipped school, “Which was UNHEARD OF. We were such goody-goodies.”

“We skipped school and went to Forest Lawn, the cemetery. There was an art exhibit going on there or something. But it started raining really hard, so we decided to go to Thrifty’s because they had ice cream. We thought it was a wonderful idea to eat ice cream in a rainstorm.

So we got inside and there was a line! And the people right in front of us were this pair of little old ladies; white hair and knitting bags. They were standing there, arm in arm, doing the same thing we were: buying ice cream in a rainstorm.

I can’t remember if Heather hit me or I hit her, but she was like, ‘That’s us! That’s us! We’re going to be old and we’re going to eat ice cream in the rain.’”

Joy took a minute to collect herself; mentioned something about the privilege of growing old. When she was ready, she smiled, sighed and said, “Yeah…” and we continued.

Shortly after Joy and Heather bought ice cream in the rain, they both went off to college. Heather went to Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan and Joy went to the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

They wrote each other – actual handwritten letters – every week. “We were religious with those letters. There was nothing I’d rather do than sit down and tell her about everything. I still have them. I don’t read them often. It’s a lot…”

In one of those letters, written during their sophomore year, Heather revealed that she’d been feeling “weird”.

“Her hands had been tingly, like pins and needles for a week, and her leg was feeling like that, too. It was only the one side. She went to the doctor and they didn’t know what it was, so she was supposed to get a brain scan.

She had the first scan and they found something. It could be water on the brain or a mistake on the scan, or it could be a tumor. They didn’t know.”

It turned out to be a tumor – Glioblastoma. The tumor was fast growing, in the center of her brain, and inoperable. All research at the time suggested that Heather would only survive six months to a year. She lived nearly two.

It was during Heather’s first trip home after her diagnosis that she came up with the line, “I have something on my mind. It’s a tumor.”

How did people respond to that?

Joy furrowed her brow. “I can’t remember. Nobody expected her to die. If anybody’s telling you a story about someone who had cancer, it’s usually how they overcame it.”

But Heather’s illness progressed, slowly paralyzing her left side and compromising her motor skills. When Joy and Heather’s mom visited her in Michigan the next winter – “I’m amazed that her mother let her go back to college. I was so proud of her.” – she “had a big, moon face from the steroids she was on, and she could barely walk with a cane.”

But Heather never believed she was going to die, so neither did Joy.

“Heather came and stayed with me at USC for a weekend. She was just like a baby bird. I had to help her put her clothes on, her underwear. That was awkward, but I was her nurse, and we were friends. ‘I’m going to stand by you, and walk with you, and we’re going to get where we’re going, and that’s that.’

She just made me happy to be around her. We’d always be laughing and joking, always, always, always. But there was one moment in that weekend where I said, ‘I’m scared, what will I do without you?’

But that’s the only time I can remember even thinking that, or saying it out loud.”

In the summer of 2001 Joy went back to Redlands to be with Heather. “We spent so much time in the garden looking at stuff. It was kind of like we were old ladies. We would just sit around and look at pretty things. She would paint a lot.”

After Heather’s birthday on September 12th, Heather decided to undergo brain surgery.

“She had two tumors. The one that she’d had for the longest she called ‘Grandpa’. And then there was ‘Mini Me’. Mini Me was the new one, and Mini Me kept getting bigger and bigger. I saw a scan of her head, and it looked like Mini Me took up 25% of the space in her skull. She started having seizures.

The doctors said they’d done everything, and the only thing that they could possibly do was a really invasive brain surgery where they would try to take Mini Me out. Heather wanted to do that.”

Joy, Heather, and Heather’s family went to the UCLA Medical Center to prepare for surgery. Part of the preparation was for friends and loved ones to give blood if they could. Joy and Heather’s mom donated blood, as they had the same blood type as Heather.

“Heather was with us when we went. She was in a wheelchair, but we couldn’t take her into the back while we gave blood, so we left her in the waiting room.

I bled the fastest, so I came out first. And as I was coming out to the waiting room, I heard her voice asking this room full of strangers, ‘Would you like to hear some poetry?’

So she straightened herself up, her painfully thin body, and she recited ‘Death Be Not Proud’ by John Donne. She recited it from memory.”

A few days later Heather had her surgery. Joy was in the room as she was wheeled off.

“I can’t remember the last thing I said to her. I think it was, ‘I’ll see you later, I love you,’ or something like that.”

Heather came out of surgery and from there Joy, two more of Heather’s friends, and Heather’s family could only wait.

As Joy explained, when a person undergoes a brain surgery like Heather’s, the surgery can’t really be called a success until the brain stops swelling and reduces back to its normal size. “Best case scenario, it reduces and [the doctors] deal with what they’ve done. Worst case, it continues swelling and you don’t wake up.”

Heather lay in a coma as Joy and her family took turns sitting with her, holding her hand, talking to her. During this time Heather would sporadically jump and flinch.

“When I was singing all these songs I knew, she would get even more active and jerk and stuff. The nurses would come by and say that they knew it seemed like she was responding, but she wasn’t really. I guess to brace you for the fact that she might not wake up.”

Heather never woke up.

“I can’t remember the exact conversation, but I remember her mom saying, ‘I talked with Heather before the surgery and she doesn’t want to be hooked up to something forever. The swelling isn’t going down, we’re going to take her off life support.’

So we all made our way into the room and they took out the tube. But she wouldn’t stop breathing!”

Joy laughed incredulously. Again she seemed proud of Heather.

“We were there for maybe two hours and she was going strong!”

At 7am Joy got a call from Heather’s mom. The family had asked that Joy and Heather’s friends give them some privacy, so they had all gone back to the Tiverton House where families of UCLA Medical Center patients stay.

“Heather’s mom was like, ‘It’s happening…’ I can’t remember exactly what she said. I just knew, ‘We have to go there right now, it’s happening now.’

So we went running through the parking lots and up the elevator. But she was gone when I got there.”

Words failed her and Joy cried softly. When she spoke again, she seemed to be picking through her memories.

“I remember it was quiet. Her hand was really tight in a fist. She just looked like she was sleeping. Her head was wrapped, parts of her red hair were sticking out. Later, her mom gave me and the people there some of her hair. I have it still. She was so proud of her red hair.

Afterwards we all went to brunch at the W Hotel in Westwood.” Joy laughed at the relative oddness of the going to that very posh hotel. “We were hungry! We hadn’t eaten in a long time. We were still alive!”

That day, and the subsequent days before the funeral were a blur. Joy spoke slowly.

“I remember the funeral…It was huge.”

Two months.

“I don’t remember what I wore to the funeral,” There was a long pause, and she seemed troubled for a moment. “I can’t remember…”

“Heather was there. They had her in a coffin. She was wearing a dress, this beautiful champagne-colored chiffon thing, it looked kind of ‘20s and it had lots of rhinestones on it.

Her mom asked three of us to speak. Someone who had never met Heather, had only known her through the email list [Heather’s mom’s support email list, which numbered in the thousands], someone who was closer to Heather, and me.

The guy who had never met Heather talked the longest – naturally, because he was a man and he didn’t know her. That’s how it always works, right?”

She chuckled and ever so slightly rolled her eyes.

“I just read from a letter she’d sent me. I don’t remember now exactly…I think it had something to do with death or life or Heaven. I put pennies in the coffin with her.”

Joy and Heather had always given each other the lucky pennies they’d found. “So we knew we were thinking of each other.”

Joy leaned her head against a wall and closed her eyes for a second. She told me a story about when Heather had a shunt put in and she had huge “railroad train track staples” going across her shaved head. Nonetheless, Joy took Heather to the store; she remembered watching Heather walk down the aisles.

“I was so proud,” Joy said, maybe not so much for my benefit, her gaze distant.

“Yeah, that’s my friend. Yeah, we’re together. Nothing is a disaster if we’re together.”

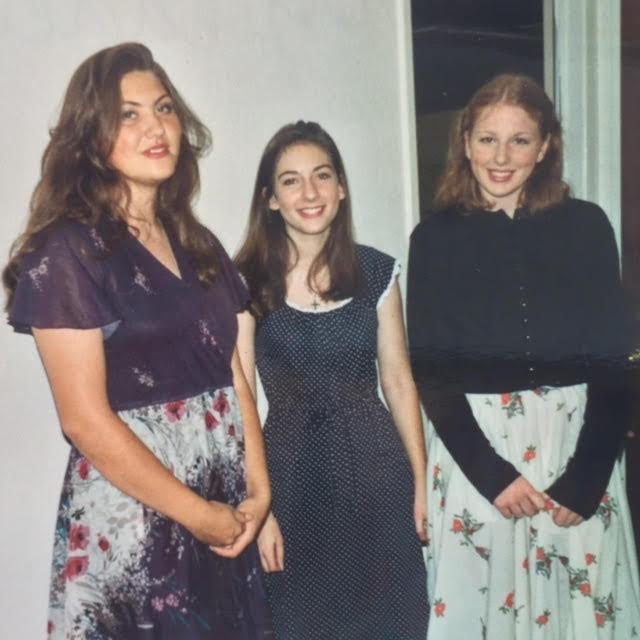

All photos courtesy of Joy Nash.

Louise Hung is an American writer living in Japan. You may remember her from xoJane’s Creepy Corner, Global Comment, or from one of her many articles on death, folklore, or cats floating around the Internet. Follow her on Twitter.