I spent most of my 20’s studying death – through mythology, ritual, art. I was intent on making people think about the things they shied away from. Not because it was morbid, but because it was fascinating: all these things that seem unrelated link up with just a little bit of digging. You pull one dark string and the whole world snaps into place.

Being willing to talk about lots of things that made ordinary people uncomfortable made me not the most fun at dinner parties back then, but it gave me a really beautiful life.

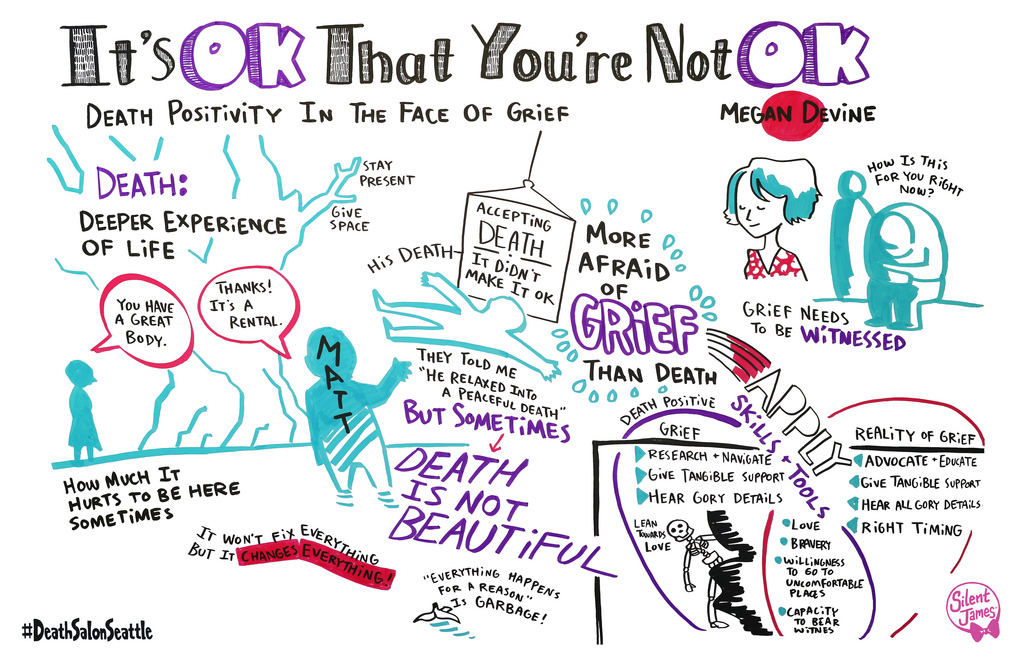

I met my partner when I was 34. He was different. I was different. Instead of looking at each other with that half-cautious raised eyebrow, slightly uncomfortable thing people give you when you’re just being your normal strange self, we relaxed around each other. We spoke the same language. Our early courtship days were full of discussions on religion, fears of death, the cultural intersections of personal loss and addiction. We talked about death a lot. The first time I saw him naked, I told him he had a great body. He said, without missing a beat, “thanks. It’s a rental.”

Eight years ago, I watched him die. He drowned on a beautiful, ordinary, fine summer day.

My understanding of death as a natural process did not help me. My familiarity with death rituals and funerary art and the darker, harder aspects of life did not make his death – or my grief – any easier. Accepting that death happens can’t make death okay. Not Matt’s death, and not deaths that many in this world see.

I don’t think it’s intentional, but I think a lot of what we have in mind when we think of death positivity is death that happens at the end of a normal, natural, expected western lifespan. In those kinds of deaths, you get to be sad, yes. But it makes more sense, in addition to that sadness, to lean on our ideas about the cycles of life, of the beauty in a life lived well. Death positivity feels really congruent in the face of those kinds of deaths.

But that’s not the only way we die.

Sometimes death is not beautiful. Sometimes death is not normal. Sometimes death is wrong.

There’s a weird, clanging disconnect when we try to apply what we know as death positive people into the gaping open wound of death itself, especially the “out of order” kinds. Accidents and natural disasters can’t be treated as a “natural process.” Hate crimes, gender-based violence, deaths hastened by lack of access to health care, death created by acts of war or targeted genocide – we can’t claim those deaths as beautiful. We can’t use our standard language here. Talking about these kinds of death – and the grief that comes with them – is one of the last real taboos.

What I hear from people grieving losses from these kinds of death is that being friendly with death – even being deeply interested in it as a cultural exploration – feels wholly irrelevant to their grief. A mother whose 14 year old son was killed by a drunk driver told me recently that the death positive movement felt “too hip to be of use.” That the art, the cafes, the memes about day of the dead, and roman crypts, and bat tattoos felt flippant in the face of what they were living.

I hate that. And, I get it. Without meaning to, we can alienate or injure people going through some of the hardest times of their lives.

There’s so much beauty, so much potential inside what we know as death positive people, but there is a chasm there, between the ways we talk about death in the abstract, and the ways we live inside actual grief.

We’ve got to start talking about grief in the face of deaths that are not beautiful.

The ways we come to grief due to violent or accidental deaths is really no different than the ways we need to come to all grief: with kindness, compassion, and acknowledgment for how hard it is to be here sometimes, how hard it is to love, and to lose those we love. In grief paired with violence in any form, it’s important to acknowledge the injustice of the death while not losing sight of the intimate loss itself: too often, the intimate loss is obscured by communal outrage. At the same time, we have to acknowledge the nature of the death, knowing that injustice is deeply stitched into grief itself.

It’s holding your primary focus on the intimate loss, while keeping your eye on the wider cultural reality, that will make you invaluable if and when non-beautiful death erupts in your life.

What we’re really doing, in both the death positive movement and its sister, the grief movement, is turning towards what feels scary and painful. We’re building skills, and gathering knowledge – not to avoid grief, but to withstand it. To able to companion each other, no matter what comes. Accidental death, baby death, atypical death, death due to violence, hate, or exclusion – they all belong in the death positive movement, but there’s one special rule for addressing them:

The Code Switch. There’s a difference between talking about death positivity, and acting from your knowledge of death. We can’t have a death positive movement without making room for uncomfortable deaths, but not all of our tenets apply. To truly support a grieving person, you need to know which aspect of death positivity matches the situation. Recognize that ideas about how death is treated in Western culture belong in certain spaces, while your knowledgeable presence – as a resource, as a support, as an ally – belongs in others.

So what does your interest and knowledge allow you to do in the face of death and grief, especially the deeply uncomfortable kinds?

- Be the crows on the battlefield, turning towards what scares others off. Because people are often afraid to upset people or freak them out, they don’t share the actual physical details of the death, especially if it was violent or upsetting. But those details might need to be told.

Action: Be known as the person who can withstand the details, ask intelligent and informed questions to help the grieving person tell the story. Your knowledge lets you listen. Let them tell the truth about what happened. Don’t pretty it up. Don’t turn away. Be willing to hear it again and again.

- Know the options. There’s often a lot of turmoil in the first weeks after an accidental or violent death; it’s heightened by shock, and sometimes by media coverage. When Matt drowned, I needed my death-skilled friends to find out what my legal options were for the care of his body. Their research helped me step out of the extended family drama and tend to his body in ways that felt congruent with who I knew Matt to be.

Action: Know what the legalities are around death and burial in your city and state. Your knowledge lets you navigate these for your friend or family member. That’s a great use of your skills.

- Take on unbearable tasks. There were four of us together at the morgue when we signed the papers to have Matt’s body cremated: Matt’s son, one of Matt’s friends, me, and one of my friends. Matt’s son turned 18 the day after his dad died, so he was asked to identify Matt’s body. He declined. I declined. Both of our friends offered to ID Matt’s body for us. Over eight years later, that gift still means more than worlds to me.

Action: You can be the person who does what your friend cannot. Offer to accompany your friend to the morgue. Identify their person’s body, or do other things they cannot bear to do. Your knowledge allows you to withstand that emotional hit. That kind of support is invaluable.

The death positive community is better trained for this kind of work – already – than many will ever be. We make death friendly and accessible so people can talk about death, but we can go a few steps further and find words – and ways – to talk about the reality of grief. We can open conversations about what it means to live in a world of accidents and acts of violence, where death is not always beautiful or normal. And we can stand by each other, rooted in what we know of death and life, creating a world where every part of being human is considered sacred, and worthy of love. That’s where the beauty is.