In the 17th and 18th centuries, the well-to-do in Europe sent their scions off to travel the Continent, see the civilized world, and round-out their classical educations. These so-called ‘Grand Tours’ became the rage, and people being then as they are now, souvenirs were sought at each of the stops to commemorate the journey.

In the past, I’ve run across the rare set of cameos or intaglios from this period. Unlike the mass-produced tchotchkes that we recognize today as ‘old lady jewelry,’ these were instead small custom-made keepsakes to be displayed in the dens and libraries of the upper classes. Some are portraits of the travelers themselves, made in those pre-photography days to memorialize a stop in Italy on the way back home. Sometimes the seals are of mythological figures, or famous generals, philosophers, or kings. All have in common their beauty and exquisite attention to detail.

Recently I was at the Brimfield Antique Show in Massachusetts. For those who have never gone there, it is a mind-boggling assortment of junk and very high end items; the problem is that everything is mixed together, and it’s up to YOU to sort the wheat from the chaff. Caveat Emptor and Good Luck.

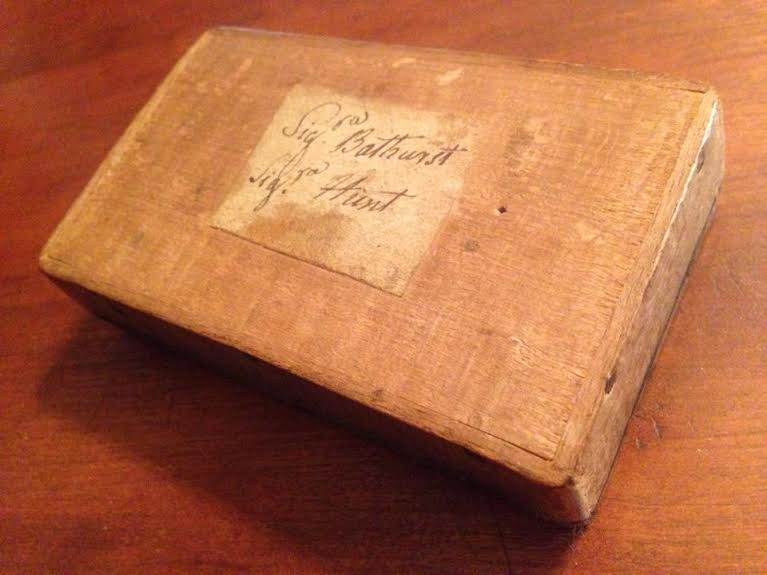

As I was sorting, I ran across a small pine box with a fragile paper label on the lid. Written in what appeared to be old quill ink on the label were a pair of names. Inside were two lovely plaster cameos with delicate gold edging, their subjects being very elegant Regency-period young women in profile. And on the inside of the lid were two more small pieces of paper, written in Italian in the same 19th century hand, both with the date ‘1824.’ Charmed, I negotiated with the seller – he admitted it was a slow day – and soon I was heading home with the new possession.

Things took a bit of a dark turn, however, once I got back to my computer and could use Google Translate to figure out exact what was written.

“Miss Bathurst, who drowned in the Tiber, March 1824”

“Mrs Hunt, who was killed by bandits at Paestum, December 1824”

This was obviously no ordinary Grand Tour souvenir.

A quick Internet search did, in fact, turn up details of these two unlucky women’s demises.

Rosa Bathurst was born the middle of three children to the late Benjamin Bathurst and his wife Phillida.

[Incidentally Mr. Bathurst, the Sec’y of the British Legation at Livorno, disappeared in November 1809 traveling in disguise through Perleberg while heading back to the Foreign Office in London. His body was never found, and it remains unknown to this day if Napoleon’s spies, or highway robbers, finished him off.]

In 1823-24, fatherless Rosa – renowned for her beauty and sweet disposition – was staying with her uncle and aunt, Lord and Lady Aylmer, at their estate in Rome. It had been a severe winter, and the first warm days were melting the snow as spring started to burst forth. On the morning of 16 March 1824, the Aylmers, Rosa, and the French ambassador, the Duc de Montmorency-Laval, gathered to enjoy a horseback ride.

Rosa and the Duc were in front on their mounts, with Lord and Lady Aylmer next, and a female friend of Rosa’s along with the Duc’s groom bringing up the rear. The riders made their way past Villa Borghese. Rosa fell back toward the rear. The party reached a vineyard – a shortcut according to the Duc – but found the gate locked. The Duc then suggested a narrow path, one that circumvented the locked gate, which lay between the vineyard and the Tiber River. The path was windy and overhung with trees and bushes. Lady Aylmer suggested that the girls dismount and lead their horses along the path, but they did not listen.

Lord Aylmer had ridden back to assure the women that only a few yards ahead the path widened and was much easier going, but as he did so, Rosa’s horse took fright and tried to turn around. Lady Aylmer called out to Rosa, warning her not to let the mare turn, but it was halfway around when it lost its footing and started to slide off the path and down the steep bank into the Tiber. Lady Aylmer jumped from her horse and tried to grab Rosa, but it was too late. Still in the saddle, Rosa fell into the river, which was swollen with spring melt water from the mountains and running swiftly.

Lord Aylmer dove into the freezing water to attempt to reach his niece, but the current was too strong for him. Back on shore, he ordered the party to remount and ride for help. Men and boats were sent out to search for Rosa. A reward of £50 was posted, but there were no signs of the girl. The expat community in Rome went into mourning. The Aylmers felt they could no longer live so close to tragedy, so with Mrs Bathurst and Emmeline, Rosa’s sister, they retired to Geneva.

The following October, two peasants found Rosa’s body buried in the sand along the banks of the river, not too far from where she had fallen into the water. The body remained dressed in her blue riding habit, with her bonnet still knotted under her chin and her rings still on her fingers. It appeared she was sleeping, according to those who saw her. Officials took charge of the corpse until the family was notified by courier and had arrived back in Rome. Rosa was then buried near the spot where she was found. Her mother placed a monument there in her honor, which reads:

“BENEATH THESE STONES ARE INTERRED

THE REMAINS OF ROSA BATHURST

WHO WAS ACCIDENTALLY DROWNED IN THE TIBER

ON THE 16TH OF MARCH 1824

WHILST ON A RIDING PARTY

OWING TO THE SWOLLEN STATE OF THE RIVER

AND HER SPIRITED HORSE TAKING FRIGHT.

THE DAUGHTER OF BENJAMIN BATHURST

SHE INHERITED HER FATHER’S PERFECTIONS

BOTH PERSONAL AND MENTAL

AND HAD COMPLETED HER SIXTEENTH YEAR WHEN

SHE PERISHED BY A DISASTEROUS FATE”

Regarding Caroline Hunt, Rosa’s boxed companion, she was the daughter of the Rev Charles Euseby Isham. Caroline and her new husband, Thomas, were doing the honeymoon Grand Tour ten months after the nuptials. Apparently the Hunts were quite wealthy, having estates in London, Northamptonshire, and Cheltenham. The couple had probably already visited Paris and Geneva, and they were working their way down the Italian peninsula in the footsteps of Keats, Shelley, and Byron. Naples has its architecture, music, cuisine, and extremely active volcano, plus nearby Paestum is home to uniquely well-preserved ancient Greco-Roman ruins. It would be the perfect stopping point for culture hungry aristocratic lovers.

Whether Caroline and Thomas had much of a chance to marvel at the Doric columns before being launched into eternity is not known. They might have appeared lost – unfamiliar with the terrain and roads – and too well-dressed and appointed for their own safety. They accordingly attracted the attention of the wrong types, and were accosted by banditti – thieves – while at Paestum. In the course of the ensuing robbery, they were killed by the same bullet, possibly as Thomas was shielding his bride from the attack.

In Wadenhoe remains a memorial plaque:

“SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF THOMAS WELCH HUNT, ESQ LATE PROPRIETOR OF THE ESTATE AND MANOR OF WADENHOE AND OF CAROLINE HIS WIFE; ELDEST DAUGHTER OF THE REVD CHARLES EUSEBY ISHAM RECTOR OF POLEBROOKE IN THIS COUNTY; WHO WERE BOTH CRUELLY SHOT BY BANDITTI, NEAR POESTUM IN ITALY, ON FRIDAY 3RD OF DECEMBER 1824. HE DIED ON THE EVENING OF THE SAME DAY, HAVING NEARLY COMPLETED HIS 28TH YEAR; SHE DIED ON THE MORNING OF THE FOLLOWING SUNDAY, IN THE 23RD YEAR OF HER AGE. AFTER A UNION OF SCARCELY TEN MONTHS, AFFORDING AN IMPRESSIVE AND MOURNFUL INSTANCE OF THE INSTABILITY OF HUMAN HAPPINESS THEY WERE LOVELY AND PLEASANT IN THEIR LIVES; AND IN THEIR DEATH THEY WERE NOT DIVIDED.”

‘Not Divided’ because Caroline and Thomas were buried together in a single grave in the English Cemetery in Naples, where they lie to this day.

The two unfortunate Englishwomen I had uncovered are not apparently related, aside from their year of death and country of passing. The wooden box in which is found their cameos was undoubtedly custom made for that purpose – but to what purpose? Why did their visages wind up together? A morbid souvenir of causes-célèbre of the day? A cautionary warning for tourists? A simple memento mori? Or nothing more than a lovely example of a long-forgotten artisan’s portraiture skills?

Likely, this part of the story will remain forever unknown.