“A woman’s final home is immortality.”

I first heard this phrase at my aunt’s funeral when I was eleven years old. As she approached our homestead in Kisumu, Kenya, a woman started singing with passionate tremolo while slow-dancing to the rhythm of her song. She scooped dust from the ground, showered it over her head, and finished by chanting the words of the dirge she had composed for my aunt, “Achopo ka osiep agoga. Jaber thurgi cho, nyakwar Oyuko min rwathe. Chunye ler ka pi soko. Tho iseloyo, tho ogol! iseloyo! iseloyo!” (“I’m here, my bosom friend. A woman’s home is immortality, granddaughter of Oyuko, mother of eminent men. Your heart is pure as water from a spring. You have conquered death, dying be damned! You have won! You have won!”)

She was performing the Luo mourning elegy, called Sigweya. Declamatory recitations in which somber words are chanted in free rhythm, but with great emotion.

Over the years, I’ve attended many funerals and witnessed various Sigweya performances, but their message remains the same, each one extolling the virtues (real and imagined) of the deceased, and perpetuating the continuity of life beyond the natural mortality of the flesh. That’s why my aunt’s friend addressed her directly in the dirge as though she was there in person. Death did not end my aunt’s existence; she continues to live, and was present at her funeral, witnessing all the happenings.

My people, the Luo of Kenya, believe that life begins in immortality and ends in immortality. This cycle starts at tipo (spirit) to ringre (body) and back to tipo (spirit) Therefore, death is merely a rite of passage, an opening to another life. When one dies, the only variation is that the body perishes, while the spirit lives on, retaining the individual’s identity. In his book African Religions and Philosophy, Professor Mbiti aptly captured the Luo belief when he wrote, “Death is conceived as a departure and not a complete annihilation of a person. The only major change is the decay of the physical body, but the spirit continues to live within the community.”

Sometimes our dead come back in the flesh. A spirit desirous of a physical frame will ask to be named by appearing through a vision, or there would be a situation where a newborn cries continuously and the household then calls out names of their departed kin until they hit the right one. They know this when the infant ceases to cry. When a child is given a spirit name (nying juok) they assume the identity of the deceased relative. It’s a common thing in the Luo community to hear a man introduce his daughter as mae dana (this is my grandmother) or a baby being referred to as wuonwa (our father). My little sister’s spirit name is nyatiegari, and whenever we travel upcountry for the holidays, she’s the first to be served food, and is usually taken around the farm to bless the crops, while other older members of the family urge her to spit in their hands as a sign of good luck since ‘she is our great grandmother.’

But not all our dead desire physical bodies. Most are content to live as spirits. However, they will return from time to time to share meals with us, or, as Jude Ongong‘a writes in The River-Lake Luo Phenomenon of Death: Rites of Passage in Contemporary Africa, they may occasionally come in the evenings to warm themselves in the company of family. Thus, the Luo say, ng’amaotho ok kuodhi (you don’t gossip about a dead person) because for all you know, they might be sitting beside you listening as you dish their dirt.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xnlfykt0u7w

Because of this belief in immortality, mourners will perform Sigweya at a funeral to console the bereaved but most importantly, to reiterate that the loss is not total since there is continuity of life. A Sigweya cannot performed by anyone, but only by those who had close ties to the deceased. The Sigweya, unaccompanied by instruments, is usually performed in a lofty style, with each narrator crafting unique personal motifs in their solo performances. The melody of the words being chanted reflects the speech contours of the performer as they move to the rhythm of the dirge.

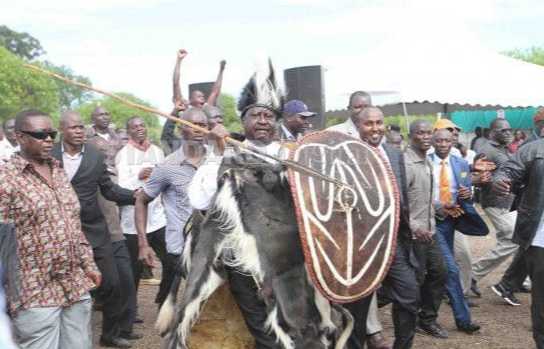

In a dense, somber mood the mourner, through individual artistry, sings the familiar scenes of the time they shared with the dead, extols their virtues, and describes the pain they feel; while in the process, recreating their life so those who never knew the deceased have an idea about who they were. The narrator finishes by charging the mourners to welcome the dead to immortality. Here is an audio excerpt of Kenya’s former Prime Minister Raila Odinga performing a Sigweya at Senator Otieno Kajwang’s funeral.

Otieno, son of Akoths’ mother, how men revere you!

My friend, son of Waondo, how Kenya depends on you.

Otieno, son of Akoth’s mother, how men revere you!

My friend, who hails from Mbita, how Kenya trusts you.

Hail the buffalo! ( 5 times)

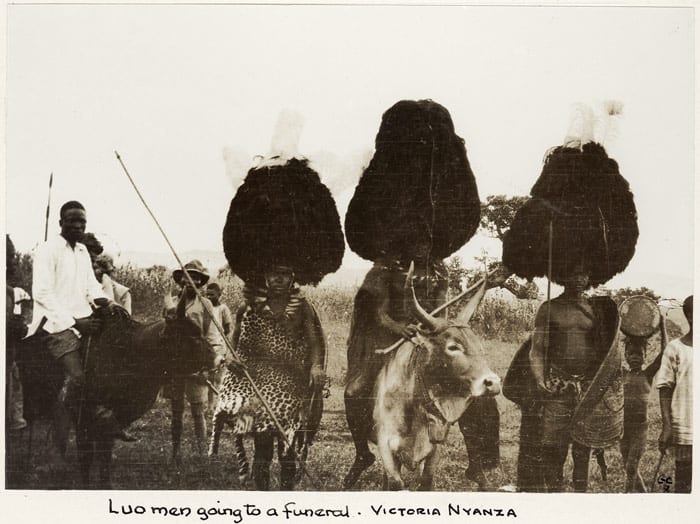

Hail the headgear! (3 times)

(English Translation)

Chanting ‘hail the buffalo’ charges the mourners to extol and accompany Otieno’s spirit as he takes on the immortal life of a courageous hero (the buffalo) while ‘hail the headgear’ refers to the ceremonial headgear made of colobus monkey skin and ostrich feathers worn by great people to symbolize wisdom and immortality.

When Kenya’s first President, Jomo Kenyatta, died, his former vice, Jaramogi Oginga went to eulogize him at the State House. Flanked by two women, he strode to the place where Jomo lay in state and immediately performed his sigweya. In December 2020, when Kenya’s second President died, Raila Odinga did a Sigweya at his funeral chanting the famous words given to a man who was now a warrior spirit, Jowi! Jowi!

The coronavirus has changed the way we bury our dead. As per the Kenyan government regulations, bodies must be buried within 48-hours of death, and with only close relatives of approximately twenty allowed in attendance.

In our culture funerals have always been a community affair, so during this pandemic we have continued to uphold tradition, ensuring that among those few in attendance at the burial ceremonies, Sigweya performers are always present to help usher our departed into honorable immortality; because even death cannot stop our dead from living.