Caleb Wilde is a sixth-generation licensed funeral director and embalmer in Pennsylvania. You wouldn’t think we’d get along, what with all my wacky first-generation West Coast alternative funeral ideas. But Caleb is sufficiently weird, sufficiently open to an evolving death industry, and a real professional. You can find his website here, and follow him on Twitter.

*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

Thinking about counterfactuals can produce maddening entertainment, especially when it comes to one’s own personal existence.

What happens if my dad didn’t spill that Coca-Cola on my mother some 40 years ago on their first date? Was that the attachment trigger that eventually produced me?

Would I exist if Columbus hadn’t sailed the ocean blue in 1492?

If cats were never domesticated, would the Internet even exist?

These. Unanswerable. All.

I do know one thing: my present existence is indebted to John Wilkes Booth.

Johnny B. and me

I’m the love child of a Romeo and Juliet-type romance. My dad’s family owned one funeral home and my mother’s family owned the other funeral home across town. Dad was the fifth-generation funeral director on the Wilde side and mom would’ve been the fourth generation on the Brown side.

With my progenitors overexposure to embalming fluid, I used to think I’d develop some genetically altered mutant power. Like a psychic embalming power that enabled me to embalm my enemies through my mind energy. Think Professor X with embalming fluid.As an adult, I realize that instead of a mutant power I’ll probably just receive an early case of cancer.

Before Booth killed Lincoln, the first generation of Wildes (we emigrated from England) maintained a small “cabinet shop,” which built caskets, dining room tables, beds and the occasional wooden dildo. We’d help the family prepare the deceased and then let them finish the course of funeralization. It was – way back in the 1850s – very much a natural burial. The ones who took care of the deceased in life were also able to do so in death.

After Lincoln’s assassination, his embalmed corpse was paraded by train throughout the states, making stops in 12 major cities, where his body was put on display for public viewing; and passing through a total of 444 communities. A bereaved nation found an outlet for their grief, and their psyche bonded to this newfangled process called embalming. Perhaps there’s no stronger bond than a grief bond; and, whether rational or not, this bond to embalming soon created the American way of death.

The Lincoln Funeral Engine

With the industrialization of furniture making, and the new demand for embalming, we adapted to the market and became full-time undertakers. By 1898, the demand produced a “funeral school” in nearby Philadelphia. My great grandfather enrolled in 1910, and by 1912 we were charging $5.00 for pumping formaldehyde through the arterial system of our dead customers.

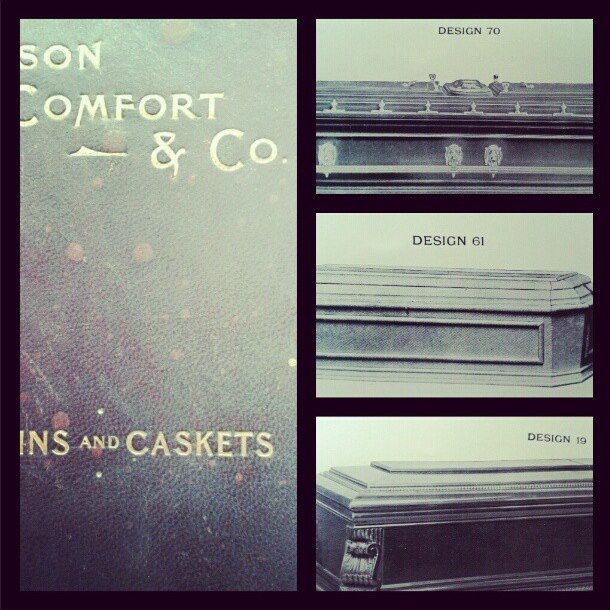

Some casket snapshots from a 1910 casket catalog that we still have in our possession.

We moved our small business to a larger town to the east and operated out of a row home. We’d go to the deceased’s house to embalm, build the deceased a casket and help direct the ensuing home funeral.

This is the gravity embalmer that we would have used when embalming the deceased at their home.

In 1928, we bought a large home and we began to offer “our” home for funerals, thus relieving families of “sad associations” during the funeral ceremonies. We advertised “Homelike Surroundings – No Charge for Use of Home.”

And here I am, the sixth generation of licensed Wilde funeral directors, still working in the same home we purchased in 1928. Once a fledgling cabinetry shop, we are now a very small part of a 20-billion-dollar national industry.

Back to counterfactuals.

What would funerals look like if John Wilkes Booth had missed?

Would the “traditional American funeral” be the entrenched tradition?

Would we need the clarion call of the Order of the Good Death?

If she wasn’t shrouding bodies, would Caitlin be shrouding … cats? Oh … wait … yes, she does shroud felines.

I probably wouldn’t exist without John Wilkes Booth; but that’s okay, I wouldn’t know the difference. Perhaps, though, we wouldn’t have industrialized death. Perhaps we’d have a better, more comfortable relationship with dying and death. Perhaps there’d be no need for the death “professionals.” Perhaps we’d be more holistic people, having a better perspective on death and a better appreciation for life.

But reality is what it is and those counterfactuals don’t exist. I’m here. You’re here. And although the American way of death is waning, it’s here too, depriving us — to one degree or another — of the life to be found in death and dying.

Thanks to you, John Wilkes Booth, we’re still fighting the effects of the Civil War.