My roommate Jillien Kahn has written her first guest post for the Order. She is halfway through her master’s in art therapy and is on her way to Mexico for the summer to work with children in San Miguel. She enjoys transgressive art and facebooking.

*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

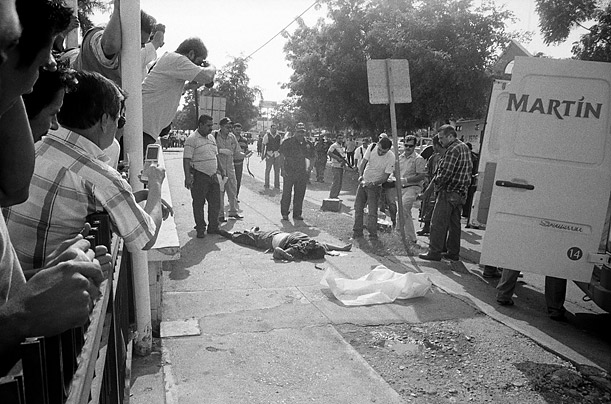

Leave it to a country ravaged by violent, drug war-fueled deaths to produce an artist with a gloriously morbid message. Teresa Margolles, an artist and morgue employee in Mexico City with a degree in forensic medicine, spends A LOT of time with A LOT of corpses, on top of coming from one of the more affected areas of Mexico, Culiacán (See: Mexico’s Drug War: The Battle for Culiacán). Many of the bodies she sees are victims of violence or drug abuse; a good number are young, some are children; and many of them are anonymous and unclaimed. She’s seen her fair share of proof that our teeny, tiny lives are fragile, and has earned the right to shove it in our faces. Literally.

Her controversial installation at the Venice Biennale, in 2009, ¿De qué otra cosa podríamos hablar? (What Else Could We Talk About?), which took as its materials blood, shattered glass and other items gathered from the scene of murders in Sinaloa, earned Margolles international attention — and death threats — and got many of her supporters in the Mexican cultural scene dismissed on the orders of President Felipe Calderón.

My favorite three pieces come from her 2004 exhibition at Franfurt’s Museum für Moderne Kunst, Muerte sin fin (Death Without End), a title borrowed from a poem by Mexican writer Octavio Paz. In multiple installations, Margolles successfully removes pretty much every defense we’ve constructed against mortality by utilizing the water used to wash the corpses of the bodies she encounters. In En el aire, happy, shiny bubbles fall from the ceiling and burst cells of death onto your skin (bursting bubbles, bursting life).

In Aire, Margolles uses this same water to humidify the room, so what feels like hot, moist air is actually hot, moist death filling your lungs (just breathe it in, lovelies, just breath it in).

In the third, Papeles, Margolles has run sheets of paper through the water used to wash corpses post-autopsy, creating wee abstract postmortem portraits. But there is MORE, so much more, which you can find in the lovely exhibition essay.

These pieces are particularly interesting because they actually make tangible the thing that we, as a culture, spend our lives ignoring/peeing our pants at the thought of. I LOVE that Miss Margolles goes beyond shocking the senses with images of death in favor of finding a way to actually make us part of death, or rather, it a part of us — which it always has been, we just need to force-feed this shit before we can admit it. See, that doesn’t hurt so bad, does it?

The exhibition essay uses some pretty words that I like and will share with you:

Using highly unusual methods of eliminating the distance we usually place between ourselves and the dead, Margolles carries her work to an existential extreme. She succeeds in transcending aesthetic boundaries with artistic means that function silently. Often it is solely the spectator’s power of imagination that lends the inconceivable a momentary presence. The works of Teresa Margolles are saddening and at the same time, by virtue of their beauty, captivating. In many instances they evade any attempt at rational explanation by forcing the spectator into virtually physical contact with anonymous corpses. The exhibition presents a great, moving, overwhelming oeuvre – provided we do not close our eyes to death.

I would like to repeat: “…provided we do not close our eyes to death.” Or our mouths, as the case may be. Point well made.

***