Lukas McLaughlin is an embalming student at the British Institute of Embalmers and the Irish College of Funeral Directing and Embalming. He contacted me first on Twitter (where you can find him at @lukasmclaughlin) and introduced himself as a 20-year-old chap with a pretty good story. Pretty good, as it turns out, was an understatement.

*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

My name is Lukas McLaughlin, and it has been for just over a year now. Before that, my name was Matthew Irvine. I was born on 8th April 1991 on a Monday evening at 22:10. The day I was born I had two parents, both aged 21 and undoubtedly in love, and an older sister who they had created three years prior.

My mother was, on occasion, absent from us due to mental health issues. This placed extra strain on my father to raise two young children. My father was a private, belonging to the Royal Irish Rangers, and soon after I was born we moved to Lemgo, Germany, to live while he was stationed in Storoway Barracks. From what I remember of the short time we were together as a family, things were good. There are boxes upon boxes of photographs from our time together in Germany, which seem to depict a young, happy family.

My mother was, on occasion, absent from us due to mental health issues. This placed extra strain on my father to raise two young children. My father was a private, belonging to the Royal Irish Rangers, and soon after I was born we moved to Lemgo, Germany, to live while he was stationed in Storoway Barracks. From what I remember of the short time we were together as a family, things were good. There are boxes upon boxes of photographs from our time together in Germany, which seem to depict a young, happy family.

In the spring of 1993 — I am now 2 years old — we went home to Northern Ireland. I assume this was due to my mother’s affliction.

A few months pass; my mother is in a psychiatric ward, where she spends many of her remaining years. My sister and I are staying with relatives, while my father is in a most horrid place. He was 23 years old, with more responsibility than he could bear. At some point this same summer, my father decided that life was too much and committed suicide. This began my relationship with death.

My mother’s condition was naturally made even worse by the news of the death of her husband. She had the courtesy to put my sister and me into the foster care system on the condition that she was allowed visitation rather than seeing us taken from her. For a while we lived with relatives. Then we were passed around within the system — two weeks here, three weeks there. When I was 5 years old, I left yet another foster home and arrived at a family’s house without my sister. I wasn’t expecting to be there long, so it took me by great surprise when my sister arrived three weeks later. Fortunately, we never left. We became part of the family, as did my mother.

Both my foster family and social services were always very forthcoming about my questions regarding my real father, which I now believe was to protect my mother’s mind from the questions of a curious child. I knew he had died, but I had been told it was a car accident. I had been in a serious car accident at the age of 3, and so I began to wonder why I hadn’t died in the same collision. It was my sister who informed me that he had, in fact, shot himself. I believe I was around 7 years old when she told me this and I remember finding it extremely strange, as it never occurred to me that anyone could do such a thing on purpose. Naturally, I began to ask questions and piece the puzzle together. Everyone around me at this point became concerned, for what reason I still do not know. It may be because I did not start to kill small animals or react in some other “textbook” way. Thus I was sent to a child psychiatrist, who put my “coping mechanisms” at well beyond my years.

I enjoyed having a psychiatrist in my earlier years, as it provided a place where I felt I could discuss my curiosity about death, what it meant, and why I didn’t feel the same way that other people did. I think people were overly cautious about the issue with me, which just further piqued my curiosity. When I got to high school, aged 11, my mother began to get better and bought a house not far from school. This enabled my sister and me to visit more often and we grew extremely close.

I enjoyed having a psychiatrist in my earlier years, as it provided a place where I felt I could discuss my curiosity about death, what it meant, and why I didn’t feel the same way that other people did. I think people were overly cautious about the issue with me, which just further piqued my curiosity. When I got to high school, aged 11, my mother began to get better and bought a house not far from school. This enabled my sister and me to visit more often and we grew extremely close.

In high school, it would be fair to say that I was, at times, a challenging student. I always achieved academically, but I didn’t apply myself. I left high school, aged 16, and attended college [the equivalent of a vocational school in the U.S.] with the intention of eventually going to university, with no clue as to what I wanted to study. Well, that’s not entirely true, I knew what I wanted to study — I just decided I wanted to fit in.

I was not been prepared for how relaxed college turned out to be. I was enrolled but did not attend classes often, as I had no real want of any qualifications I wasn’t prepared to use. I got by on one or two classes per week and took a part-time job to make money for partying on the weekends. One such weekend, the January before my 18th birthday, I had stayed at a friend’s, about a 20-minute walk from my house. As I walked toward my house, I noticed a strange vehicle parked outside that looked to be an unmarked police car. I immediately began to think of anything I might have done to warrant such a visit, but came up with nothing. When I got inside, I was asked by my family and the police officers to sit down; there was a cup of tea already prepared. I asked what was happening, as I felt very uncomfortable and my foster mother’s eyes looked teary and red. It was then that I heard the words, “It’s about your mother.” Immediately, my mind flooded with all sorts of thoughts; I settled on the most prominent, “What has she done?” I was informed that she had been found dead in her home, where she lived alone, and that there was no sign of foul play.

My response to the news of her death was to ask questions. I do remember crying at first, until my sister arrived. I felt the need to be strong for her; I knew that she would handle the situation differently.

We were taken to our mother’s house to confirm that it was, in fact, our mother. I remember being very calm and talking to the police as if nothing had happened; my sister was inconsolable and, honestly, began to irritate me because of my inability to understand why I wasn’t reacting the way she was. Was I normal? Did I care as much as my sister did?

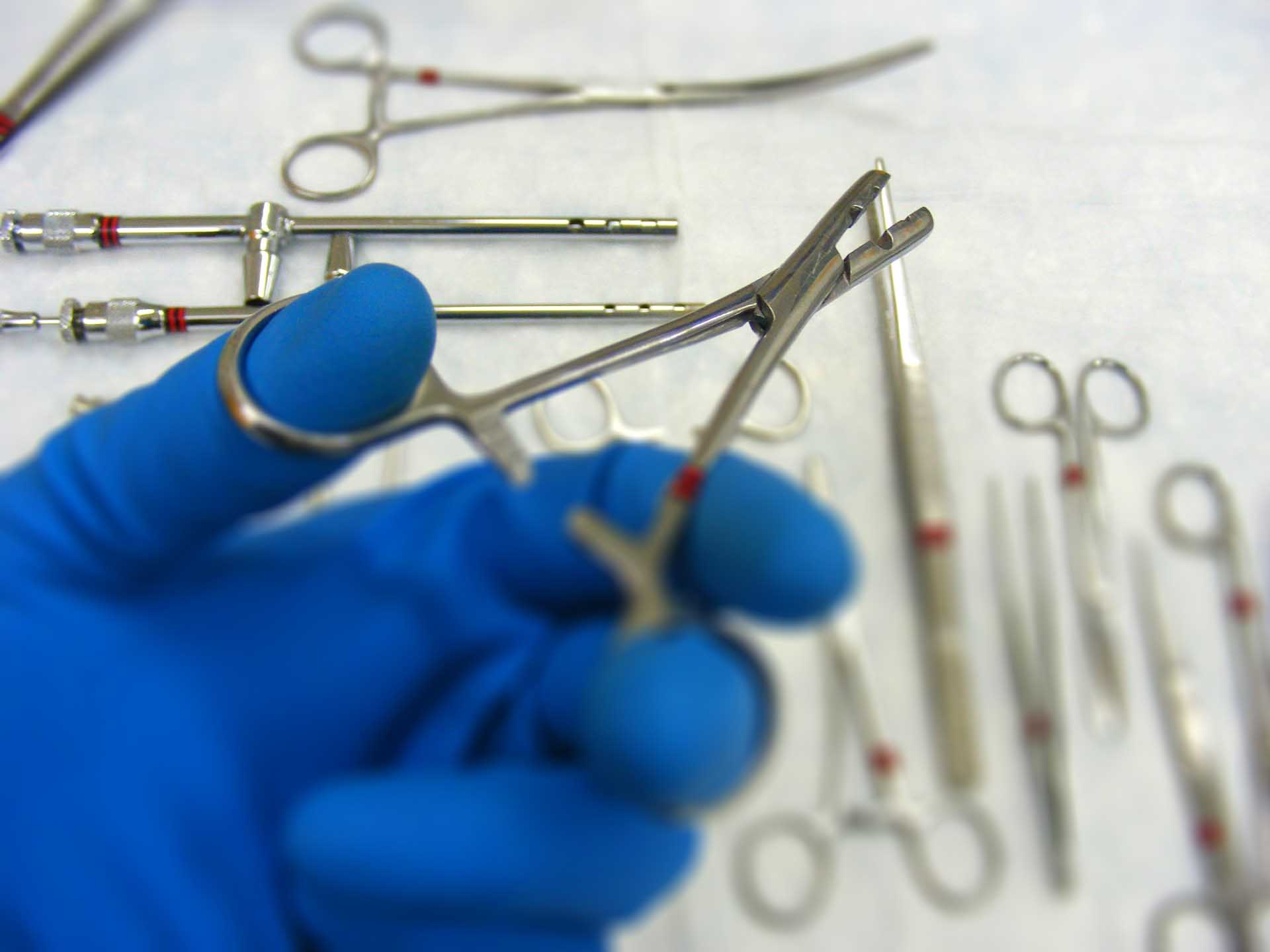

Throughout the process, from being orphaned to the end of my mother’s funeral — which my sister and I dealt with as legal next-of-kin — I let my curiosity run wild. I was helping out where I could, even assisting the body removal guys at the house. I would ask questions about the funeral service and became close with a woman who worked in reception at the funeral home. My sister had been unable to leave the body, so she stayed with my mother right up until the funeral. I stayed too to be with my sister, and to make sure she was eating and such. I also used this time to talk more with my new friend in reception. The more we talked, the more I ventured to ask, and once we hit the topic of embalming — there was no return.

It turned out that my friend in reception was also an embalmer — the very same one who had embalmed my mother. I took the opportunity to ask as much as I could about embalming, and to inquire as to how one would get into such a business. She offered to speak to a tutor she knew on my behalf, and was able to finally complete my relationship with death, for which I am eternally grateful.

I no longer worry about whether or not my interest in death is normal because, quite frankly, I do not care. My sister sees me as insensitive because I did not mourn the loss of my mother for more than a day or so, which can hurt at times, if I am being entirely honest. I am not insensitive; I merely recognize the relationship I’ve had with death throughout my life and choose to embrace it rather than hide from it. I hope that in time, perhaps in future generations, we can talk openly about death and what it means, and avoid all the nonsense of bubble wrapping what should be as natural to talk about as birth.

One more note as to why embalming means a lot to me, personally, and why I find this imagery so beautiful. As part of my mother’s mental health issues, she thought the blood inside her was “bad” or “wrong,” and was repulsed by it. She would do her best to remove it. Through my studies of embalming, I was able to help my sister’s grief by explaining, however deluded it may be, that our mother finally had the blood she so loathed removed.