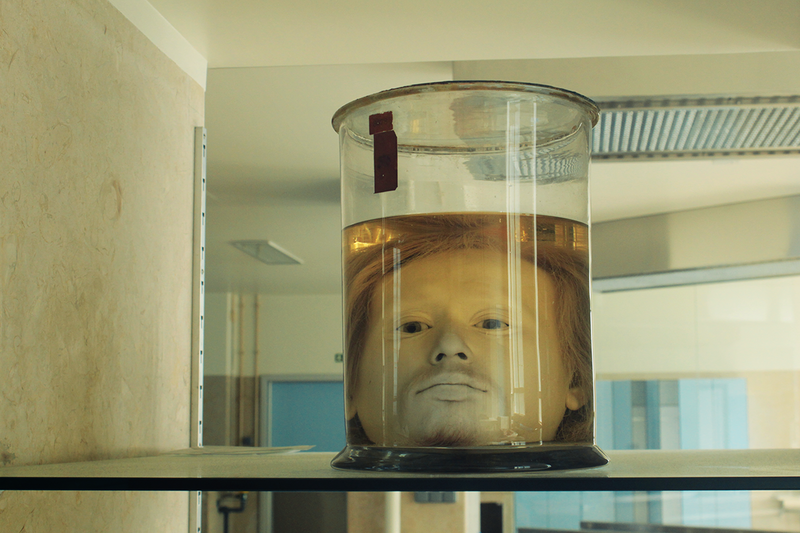

When I first wrote about Diogo Alves, the 19th century Portuguese serial killer who was sentenced to death and had his head preserved in a jar, I didn’t expect the entire world would pounce on his story. It held interest to me –I am a criminology graduate with a master of Forensic Sciences and part-time researcher of the display of dead bodies–but it was hard to imagine a mainstream audience being interested in this man’s pickled head.

Then again, it was the photos. It’s always the photos.

Alves found his way far and wide: he was on Wired and Dangerous Minds, on Portuguese and French and Indian newspapers, on Time Out magazine under “attractions” in the Portuguese capital. A few months went by and he got to travel outside of Lisbon, to star in a Coimbra-based exhibit about the 150th anniversary of the abolition of the death penalty in Portugal. When the news broke, people congratulated me, like I’d somehow enabled his little outing.

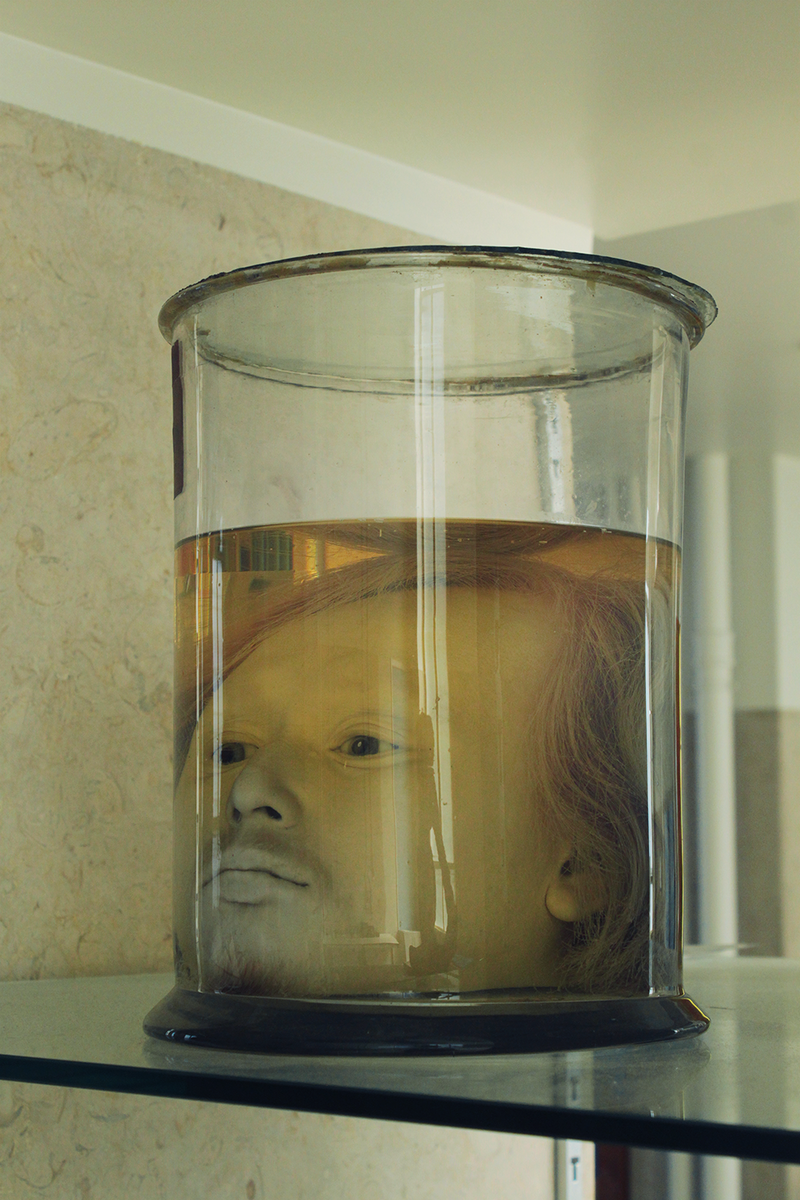

I went to visit, of course. Alves was tucked away in the “dark” side of the exhibit (as opposed to the “light” side, which chronicled the abolition movement). The fluid inside his jar had been replaced since I’d last seen him, rendering his features a little clearer, and I smiled at the detail. Rather than an act of museological preservation, it felt like an act of kindness towards a fellow human being.

A part of me appreciated it. Another wondered if he deserved it.

The over-humanization of men who do horrible things is pervasive. It’s present in the way we glorify their unlikeability and lone wolfishness in fiction, in shows like Dexter and Hannibal, but also in the way we dedicate endless minutes of primetime television to the lives and times of mass shooters, serial killers, and other sensationally violent offenders. We’re helpless in the face of our own curiosity. We yearn to know more, and there’s nothing surprising about it: in a society that still upholds the male experience as universal, these men’s criminal exploits merely add another layer of complexity to their already full-fledged personhood.

This was very much on my mind, the day I smiled at Diogo Alves.

It wasn’t uncommon, in college, for classmates to break into delighted smiles every time the curriculum took a turn towards the serial killer, that most glorified of male offenders. “I just love them,” these classmates would whisper, taking notes to fuel late-night Google searches. This fascination was assumed to be shared by the rest of us, fellow students of crime and punishment, and for good reason: society at large seems to be downright obsessed with serial killers.

It wasn’t uncommon, in college, for classmates to break into delighted smiles every time the curriculum took a turn towards the serial killer, that most glorified of male offenders. “I just love them,” these classmates would whisper, taking notes to fuel late-night Google searches. This fascination was assumed to be shared by the rest of us, fellow students of crime and punishment, and for good reason: society at large seems to be downright obsessed with serial killers.

We have come to ascribe an awful lot of positive traits to the archetypal serial killer: he is mysterious and elusive, but still charming; he may be handsome in that tousled, boyish way, or strait-laced and cuff-linked to perfection; he may be a selfish bon vivant or a strict, almost ascetic character, but his disregard for others is always portrayed as aspirational, a mere consequence of his greatness of intellect. Far from someone who can’t fit in, he has actively chosen to stay out. Pages and pages are penned on his methods, his motivations, and his work-life balance.

It’s an interesting fantasy, but still just a fantasy.

Diogo Alves was none of the things we’ve come to expect from highly romanticized serial killers. In 1830s Lisbon, his proverbial work-life seesaw tipped only once, and never recovered. His original reputation as an honest worker and a man of his word was quickly replaced by that of a violent, petty man who cared for little more than drink and cash—and would resort to brutality for both. There was no glamorous finesse to his crimes, no intellectual prowess to be admired: he’d wait in the walkway atop the Águas Livres aqueduct for an unsuspecting victim and pull a knife on them. As soon as they’d handed over their valuables, he’d wrestle them towards the 200-hundred feet drop. There was some mystery about his person, sure, but only in the sense that there was never enough evidence to convict him. When he finally went to court, and then to the gallows, it was for a robbery-turned-quadruple-murder in a wealthy physician’s house.

Alves is often promoted as the last man Portugal sentenced to death, all the way back in 1841. He wasn’t, but the dates aren’t that far off: the very last man would meet his end in 1846, and capital punishment would go on to be abolished in 1867.

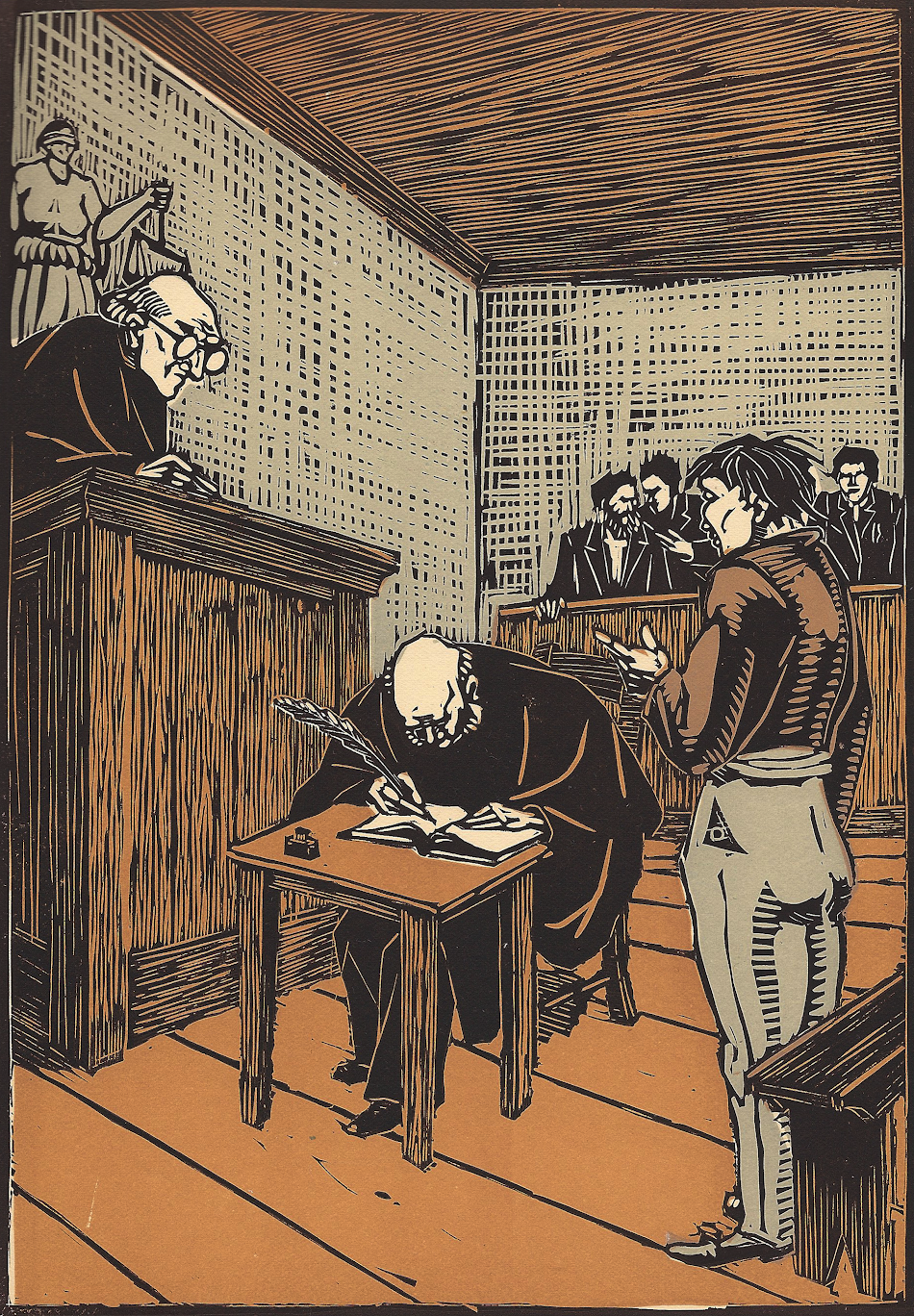

There was a reading, during Alves’ trial. A man, possibly Alves’ defense attorney (sources are unclear), stood before the court and read an excerpt from Cesare Beccaria’s 1764 treaty On Crimes and Punishments, hoping to sway the jury away from a death sentence. Even though he failed, he’d chosen his material well: Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham (yes, that Bentham) formed the backbone of the Classical School of Criminology, and both were against the death penalty. They believed offenders committed crimes not because of a moral failure or an innate propensity, but because crimes were objectively worth committing. To correct this, Beccaria and Bentham suggested a legal system that emphasized the detection and prompt punishment of each and every infraction—no exceptions, no delays. The certainty of being swiftly caught and brought to justice would surely dissuade the would-be offender, with no need to resort to the pointless cruelty of capital punishment.

This is a very logical mindset, but also a very empathetic one. Unlike other schools of thought, whose representatives argued for the animalistic, barely human qualities of “the criminal man”, Beccaria and Bentham’s focus on rationality and dissuasion acknowledged the offender as a fellow human being, no matter who they were or what they’d done. Furthermore, it drew attention to the reality of the death penalty as an unpredictable, arbitrary, and abusive form of punishment–characteristics it still hasn’t shed, and probably never will.

_______________________

Word on the street says Alves pushed close to seventy people from the walkway atop the aqueduct, but there is no way to prove this figure, no way to distinguish his victims from those claimed by another, quieter killer—suicide. All through the 1830s and 1840s, the Águas Livres aqueduct offered an option to those set on taking their own lives, and many were desperate enough to accept. This tragic reputation would come to provide much needed camouflage for Alves’ operation.

We know his victims only for their collective name: saloios, inhabitants of the rural suburbs of Lisbon who walked in and out of the city every single day, intent on selling their produce in its many markets. Although some were certainly comfortable, they were far from wealthy, which is perhaps, the only explanation we need to understand the lack of written sources regarding their deaths.

We have the story, however, of the people whose deaths would eventually lead Alves to the gallows. It all happened on the night of the 26th of September 1839. The address, 16 Rua das Flores, was home to a wealthy physician by the name of Pedro de Andrade, his footman Manuel Alves (no relation, at least familiar, to Diogo Alves), his housekeeper Maria da Conceição Correia Mourão, and her two daughters, 19-year-old Emília and 17-year-old Vicência. On the night of the murders, there was also a visitor: José Elias, the housekeeper’s 25-year-old son, a sailor just landing from a long assignment at sea.

That night, the physician had gone elsewhere on a social call; the housekeeper had requested his permission to use the dining room to serve a homecoming supper to her son, which he had granted; and the footman, taking advantage of all these arrangements, had made plans of his own. For a cut of the profits, he’d agreed to unlock the doors for a local gang, who’d long wished to divest the wealthy physician of his seemingly endless riches.

This gang was, of course, led by Diogo Alves, but there’s little need to delve into his modus operandi for the night. The robbery soon turned violent. José Elias, the housekeeper’s son, fought tooth and nail to repel the thieves, but there was no reward for his bravery—all four members of the family would die at Alves’ hand.

Upon discovery the next morning, the bodies were autopsied and flung into a common grave. The wealthy physician, it seems, refused to pay for their burial. As for the footman, Manuel Alves, he survived the night but wouldn’t survive his association with Diogo Alves. Unsure of his loyalties, the gang killed and disposed of his body soon after the robbery, never to be mentioned again.

It’s unclear why the family from Rua das Flores, whose names and faces the law knew, mattered more than the dozens of saloios whose lives were cut short in the aqueduct. It is clear, however, that even these four didn’t matter enough. Sources suggest that it was the physician’s reputation that carried the crime to court: Lisbon would not tolerate violence against the house of one of its finest. Today, we know the precise number of knives, candlesticks, brooches and gold watches which were stolen from the physician’s cache, but we don’t know where the bodies of Maria da Conceição Correia Mourão and her three children were put to rest. If we wanted to pay our respects to this family, to honor the cheerful supper they’d planned for their reunion, we’d have no choice but to visit 16 Rua das Flores, the site of their murder. It’s a pink house, these days, and despite the growing touristification of the area, there’s nothing on the floor level but a nondescript door. There, perhaps, we would deposit our flowers.

As I see it, and as I tell it, the story of Diogo Alves is a story of bodies that matter and bodies that don’t. The aqueduct victims didn’t matter. The Flores victims didn’t matter. Alves himself didn’t matter, not in the empathetic sense: that we know of him today is merely a testament to the dehumanization of criminal offenders in the 1800s.

It was the 19th century’s scientific obsession with the physical features of criminals that led to the preservation of Alves’s head, allowing him to evade the common grave and claim a spot in a medical school instead. Up on a shelf, joined by many of his contemporaries, he found himself a new allegiance: no longer just a serial killer, no longer just one of the last men killed by the Portuguese death penalty, he now became a preserved human specimen.

Jeremy Bentham, he of the Classical School, also requested that a friend preserve his body for posterity. A twist of fate made it so his head ended up separate from his body, but no matter. Bentham got exactly what he wanted.

There is a privilege to being able to dictate what happens to our corpse, a privilege that, historically, hasn’t been shared with the people whose bodies actually make up the bulk of anatomical and anthropological collections. I don’t know if Alves would have consented to his own display, but I can speculate: Catholic as he was, it’s likely he would have been shaken by the sight of his own head on a shelf.

Some will say he deserved, and continues to deserve, this presumed offense to his self-determination. Maria da Conceição Correia Mourão and her children didn’t get the right to a proper burial, why should their murderer?

Yet I feel differently.

I feel they all deserved better.

_____________________

That Diogo Alves’ victims did not receive proper burials is as much a product of the time as his own execution and his head’s consequent display. The mindset that allowed for one disrespectful act allowed for the other, and showed remorse for neither. Today, the state would have assured the victims were sent off with dignity, even if friends and family couldn’t afford it; today, Alves would have been sentenced to a maximum of 25 years in prison. He would not have been studied, nor put on display, unless he’d explicitly signed his consent.

Portugal is no longer the country these people knew, but the pickled head-in-a-jar, which I’ve gone to visit six times now, is a relic of a time they would have recognized.

I’m still not sure why I smiled at it, that day.

Perhaps I was just over-humanizing a man who’s done horrible things. Or perhaps I was trying, to the best of my ability, to engage with an object that I still can’t fully comprehend, along with all the history it holds in that crystal-clear, just-replaced batch of preserving fluid.