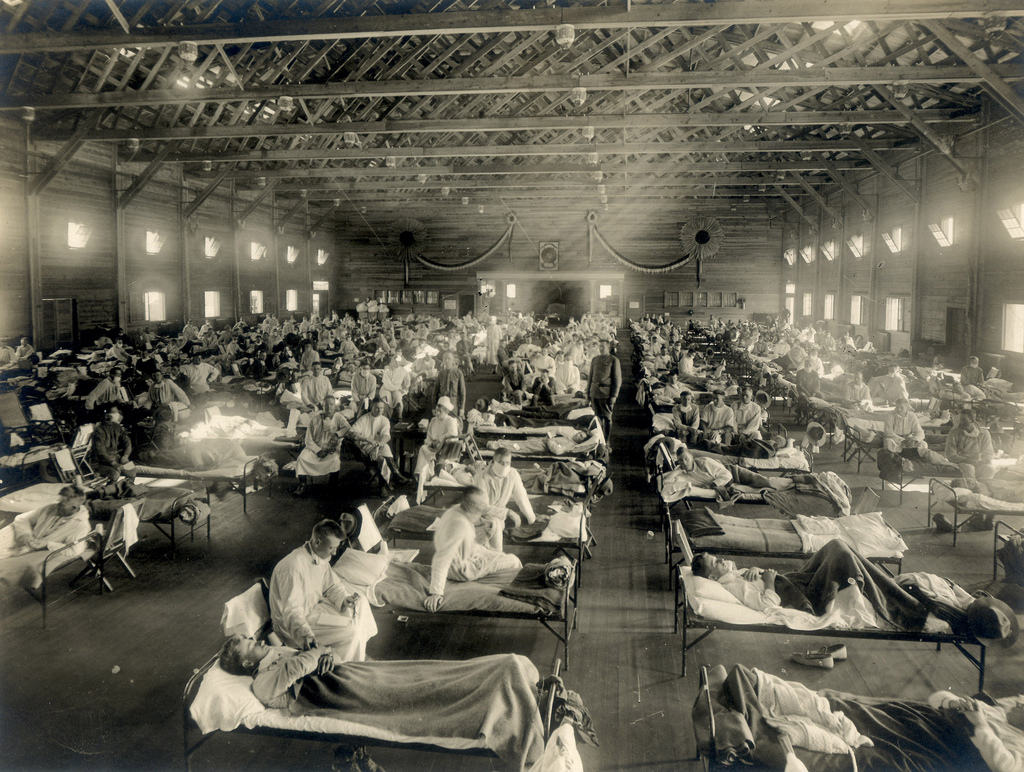

In a single day, physician Victor Vaughan witnessed 63 soldiers die. Though it was 1918 and World War I still raged in Europe, these men had not been shot in the trenches or poisoned by mustard gas. They had died from an infection, just outside of Boston, at Camp Devens. And the disease was spreading.

By late fall of that year, Vaughan solemnly stated: “If the epidemic continues its mathematical rate of acceleration, civilization could easily disappear from the face of the earth.” Humanity did not perish that year, yet it’s easy to understand why Vaughan thought it could. International death toll estimates for the Spanish flu pandemic (that is, a global epidemic) range between 20 to 100 million, or about five percent of the world’s population, with cases on five continents. These fatalities included an estimated 675,000 Americans, or ten times as many who died in World War I.

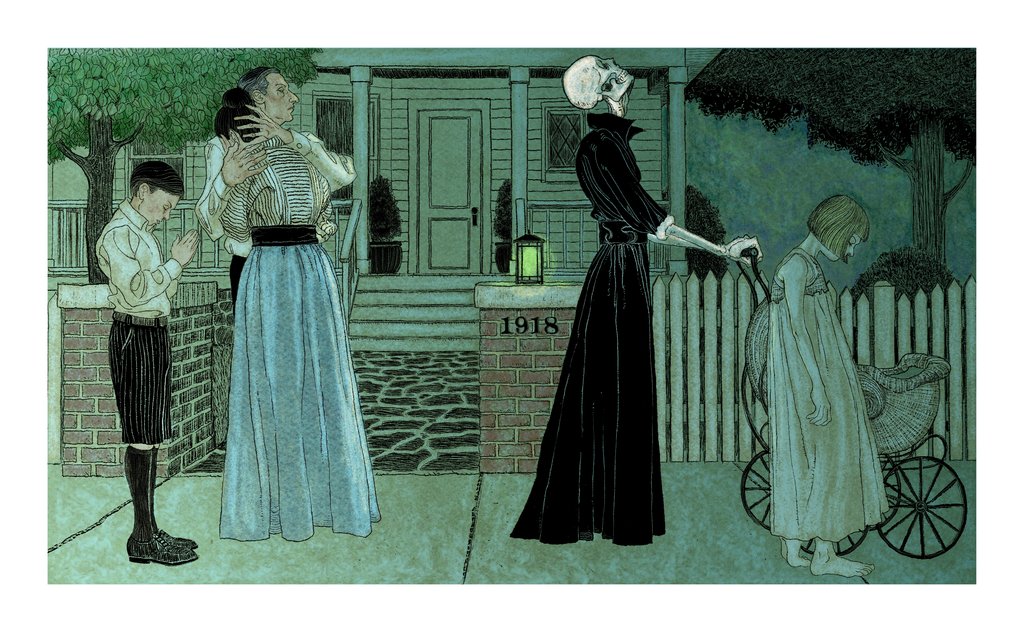

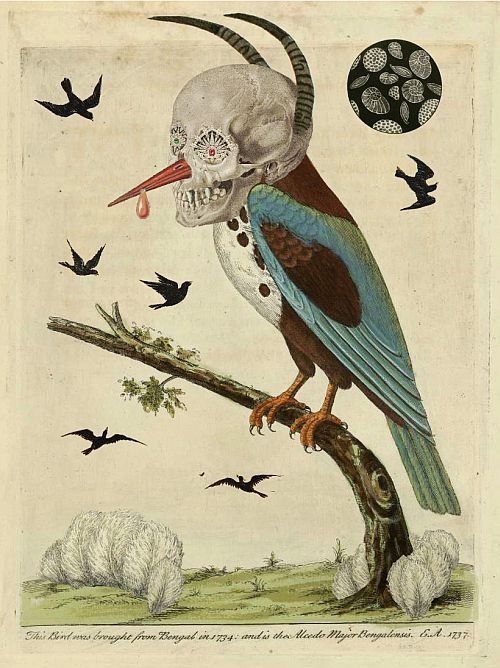

On the centennial of this health disaster, it’s worth asking: why isn’t the 1918 flu better remembered? Loss scars our family trees. The visuals of that year remain haunting, with faces hidden by protective masks, and the streets left deserted as crowds became associated with death. Schools, theaters, and even churches were shuttered as people waited for the illness to pass. Schools and private homes were turned into makeshift hospitals, while a popular skip rope rhyme was ominously sung by children: “I had a little bird, / Its name was Enza. / I opened the window, / And in-flu-enza.”

Austrian painter Gustav Klimt, his protégé Egon Schiele, and French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, all died from the 1918 flu. Edvard Munch painted a “Self-Portrait after the Spanish Flu” in 1919, in which he is gazing haggardly at the viewer, drained but still alive. Even President Woodrow Wilson got the flu, its symptoms taking their toll as he participated in the 1919 negotiation of the Treaty of Versailles. Rich or poor, rural or city dweller, no one was safe from the Spanish flu.

In Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World, Laura Spinney notes that there “are very few cemeteries in the world that, assuming they are older than a century, don’t contain a cluster of graves from the autumn of 1918 — when the second and worst wave of the pandemic struck — and people’s memories reflect that. But there is no cenotaph, no monument in London, Moscow, or Washington, DC. The Spanish flu is remembered personally, not collectively.”

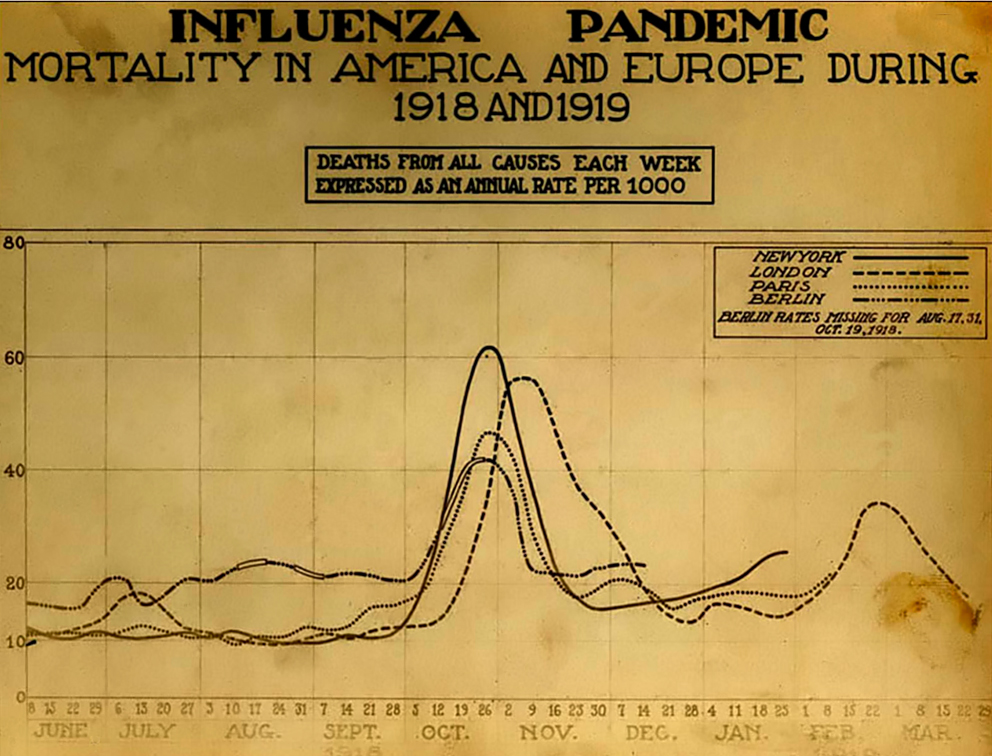

There were three waves of the Spanish flu, with two in 1918, and a third in early 1919. “Spanish flu” is something of a misnomer. The countries involved in World War I were reluctant to publicize their own struggles with influenza, lest they be perceived as weak. Spain, however, was neutral, and didn’t censor this news. Scientists and researchers have theorized for years over the actual origin of the disease, from Camp Funston in Kansas, to China, with no consensus, except that it wasn’t Spain.

Wartime restrictions on communication had deadly effects, including in the United States. President Wilson’s Committee on Public Information and the Sedition Act passed by Congress both limited writing or publishing anything negative about the country. Federally-issued posters asked the public to “report the man who spreads pessimistic stories.” John M. Barry, author of The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History, writes in an article for Smithsonian Magazine about a particularly tragic consequence of this militant protection of morale. In Philadelphia, doctors pushed for the Liberty Loan parade on September 28 to be canceled, as they were concerned the concentration of people would spur the disease. “They convinced reporters to write stories about the danger,” Barry writes. “But editors refused to run them, and refused to print letters from doctors. The largest parade in Philadelphia’s history proceeded on schedule.” Two days later, the epidemic had indeed spread, and over just six weeks, more than 12,000 citizens of Philadelphia died.

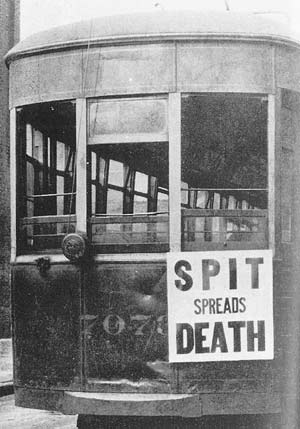

The Spanish flu is now identified as a form of H1N1 influenza. It still has outbreaks, but the clustering of soldiers in camps, the density of urban areas, and the newly global connections of ships, railroads, and other transportation, meant it had prime conditions for a pandemic in 1918. This was also before flu vaccines, and treatment options were limited. (Eating or wearing onions, drinking whiskey, and praying were some available prescriptions.) Posters issued by Alberta, Canada’s provincial board warned “there is no medicine which will prevent it,” and instead gave instructions on how to make a mask. A U.S. Public Health ad declared the disease “as dangerous as poison gas shells.” Shaking hands, borrowing books from the library, and spitting on the street were all warned against. In New York City, Boy Scouts patrolled the streets, handing spitters printed cards that read: “You are in violation of the Sanitary Code.”

Many infected people got better; many did not. In Flu: The Story Of The Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus that Caused It, Gina Kolata relates the grisly death by Spanish flu: “Your face turns a dark brownish purple. You start to cough up blood. Your feet turn black. Finally, as the end nears, you frantically gasp for breath. A blood-tinged saliva bubbles out of your mouth. You die — by drowning, actually — as your lungs fill with a reddish fluid.” And a significant number of the dead were not young or elderly — they were in the prime of their lives, between 20 to 40 years old, and generally healthy before they caught the flu.

As the sickness accelerated, there was a desperate need for doctors and nurses, many of whom were occupied by the war effort. Medical workers often contracted the flu, and there was reluctance to volunteer around this contagious disease. Then another crisis emerged: how to bury the dead. Alfred W. Crosby in America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918 chronicles the burial crisis in Philadelphia, where by mid-October the “problem of first priority was not a shortage of volunteers to keep the living alive, but the inadequacy of existing means to put the dead into the ground.” There weren’t enough coffins, and grave diggers couldn’t keep up. “One manufacturer said he could dispose of 5,000 caskets in two hours if he had them. At times the city morgue had as many as ten times as many bodies as coffins.”

At Dublin Union Hospital in Ireland, coffins were stacked 18-high in the mortuary at the pandemic’s peak. In Spain, the usual two to three-day-long funeral ceremonies were suspended, and village church bells, which had tolled for the dead since the 16th century, were stopped in order to not further demoralize the population. In Oklahoma City on the Sunday of October 13, the church bells were also eerily silent, as the city commissioners shut down the schools, churches, and any public space where the disease could spread. Just as World War I was splitting countries apart, the Earth was united under a dark shadow of death.

Some places were hit worse than others. In Western Samoa, now part of the independent state of Samoa, an estimated 22% of the population died. Māori people in New Zealand also suffered, with a death rate of about 50 per 1,000. Māori elder Whina Cooper, as quoted on the New Zealand History site, later described the horror at Panguru, Hokianga: “My father … was the first to die. I couldn’t do anything for him. I remember we put him in a coffin, like a box. There were many others, you could see them on the roads, on the sledges, the ones that are able to drag them away, dragged them away to the cemetery. No time for tangis [the Māori funeral rite].”

These cemeteries, whether in New Zealand or Kansas, are where we can remember the Spanish flu. There is no major Spanish flu monument, no Spanish flu museum. It’s likely you didn’t learn about the Spanish flu at school, even while studying the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinandand World War I. Go for a walk in your old local cemetery, read the tombstones, look for dates in 1918. You might find whole families who died within days, or maybe one big monument for a large field of grass, under which hundreds were interred when there was no time for individual headstones. There were unmarked mass graves dug for the pandemic’s dead — one was found during 2015 road construction in Pennsylvania — but many came to rest in these cemeteries, and are still there to discover and recall what popular history has forgotten.

No other epidemic or pandemic has claimed as many lives as the Spanish flu, not even the Black Death in the 14th century or AIDS in the 20th century. Its obscurity may be an urge to move on from this massive, seemingly inexplicable catastrophe. The individual losses were mourned, not the collective toll. Yet collectively is how people can make it through these disasters in the future, whether it’s getting a flu shot or supporting accessible healthcare to support a healthy whole. A flu pandemic could happen again. And unlike in wars, there are no winners in pandemics, only survivors.