“One of our wounded, whose father brought him home to be nursed, bore to me a letter from my husband and a package from General Stuart,” writes Myrta Lockett Avary. The year is 1864 and America is divided. No one can escape the political schism that is shaping the landscape, and no one can escape the loss that accompanies it. She continues writing: “The package contained a photograph of himself that he had promised me, and a note, bright, genial, merry, like himself. That picture is hanging on my wall now. On the back is written by a hand long crumbled into dust, ‘To her who in being a devoted wife did not forget to be a true patriot.’ The eyes smile down upon us as I lift my little granddaughter up to kiss my gallant cavalier’s lips, and as she lisps his name my heart leaps to the memory of his dauntless life and death.”

The Civil War had an incredible impact on how death was managed and understood in the United States. Spanning from the spring of 1861 to the spring of 1865, the Civil War remains the largest and most gruesome war to take place on American soil. The war mounted in over 620,000 casualties, or 2% of the population; in the contemporary moment, this scale of loss translates to the entire populations of both Los Angeles and Chicago. This massive loss of life transformed the culture of the United States. With the emergence of photography in the early 19th century, photography became both wildly popular and hugely influential. Photographs, or likenesses, were taken and shared as memorials and keepsakes. Photography also brought the horrors of war into the homes of civilians. The first war to be photographed, the visual remnants of battle greatly impacted how war was both seen and understood.

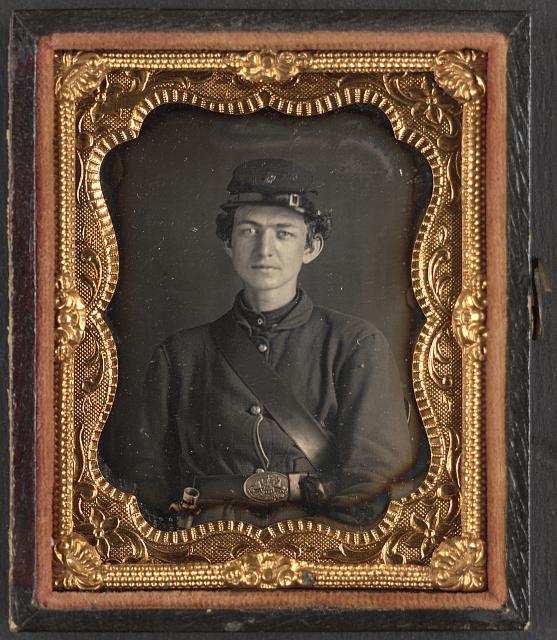

Photography was invented in 1839, and became popular rather quickly. The first type of photograph that was widely available was the daguerreotype: the photosensitive chemicals were thinly spread over a small copper plate, coated in silver. This mirrored background created a dreamy, spectral likeness that reflected the face of the viewer over the photograph itself. These small pieces were kept in folding cases, with the photograph on the left, and a small velvety cushion to safeguard the fragile photograph. These objects housed traditional portraits. For those that were wealthy enough to afford a daguerreotype or a tintype, soldiers would head to the photographic studio to have a likeness taken of them. These portraits often depicted the young man in his uniform, straight faced and looking directly at the camera. The long exposure times of the era required the subject, or sitter, of the photograph to maintain the pose for up to two minutes. Remaining still was vital, or the image would be blurry. The serious, straight face was an easier pose, not to mention the possible sobering thought that this photograph may be your last.

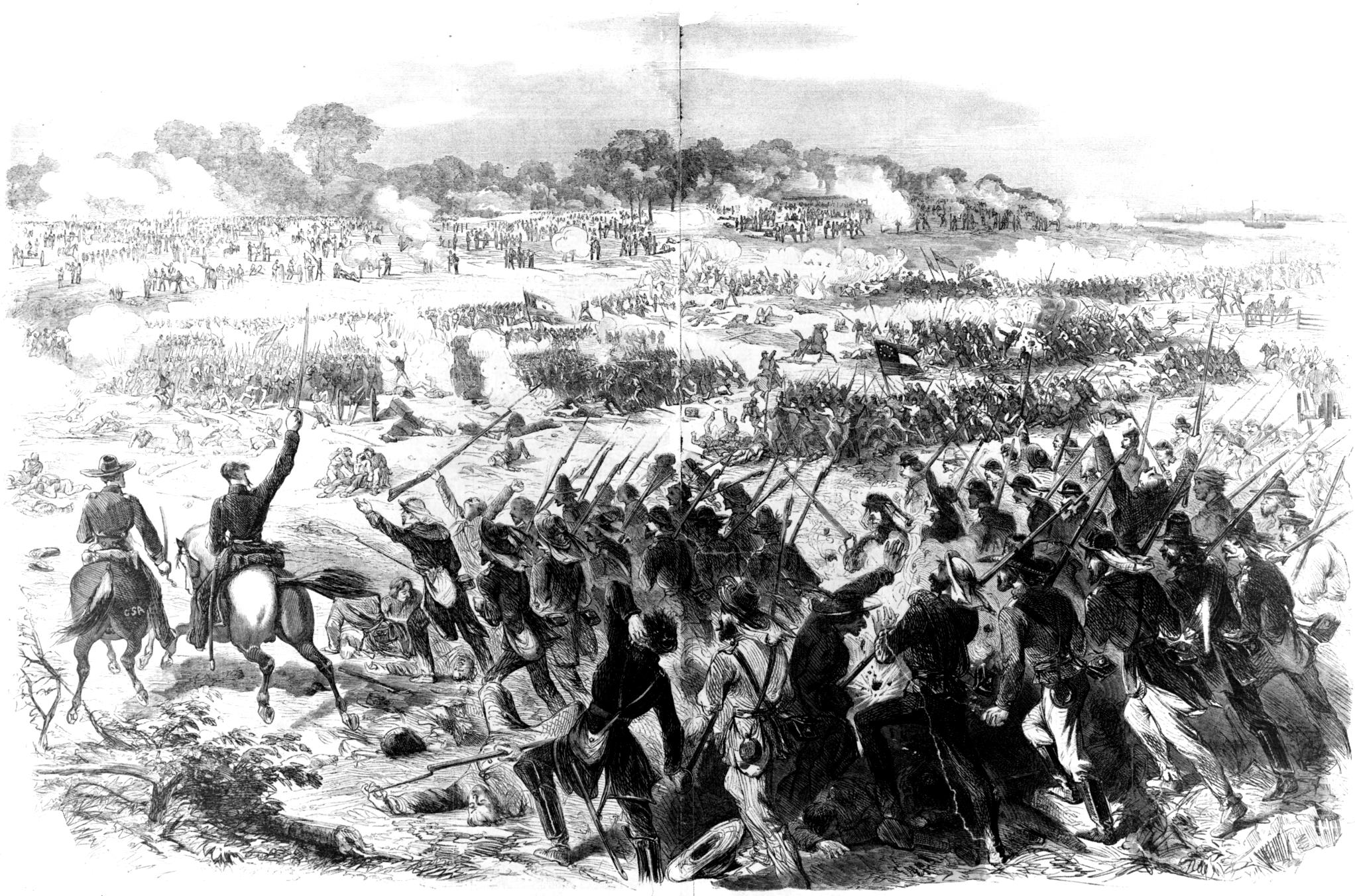

The war was not only a political and cultural turning point but was also the first American war to be photographed. This marks the first time that civilians were able to see the horrors of the battlefield, of which there were many. With death constantly looming due to supply shortages, disease ridden hospitals, and dreadful weather conditions, the plight of the soldiers was frequently dire. It was common during the Civil War for writers to describe the barbarity that soldiers were faced with in periodicals and newspapers. Some illustrated publications, such as Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper or Harper’s Weekly, even took up the duty of printing artistic renderings of the war. Highly detailed ink drawings depicted the men marching though through the brush, guns in hand. The illustrators could only provide little detail, and depicted many anonymous, small figures as they traversed the rocky terrain. Such publications offered only a glimpse of major battles and day-to-day operations which many families did not see. With the war being fought by hundreds and thousands of fathers, brothers, and sons traveling far to battle, the families back home lacked first-hand accounts of the brutalities of the Civil War. The photograph could bring this home for families in ways that other media could not.

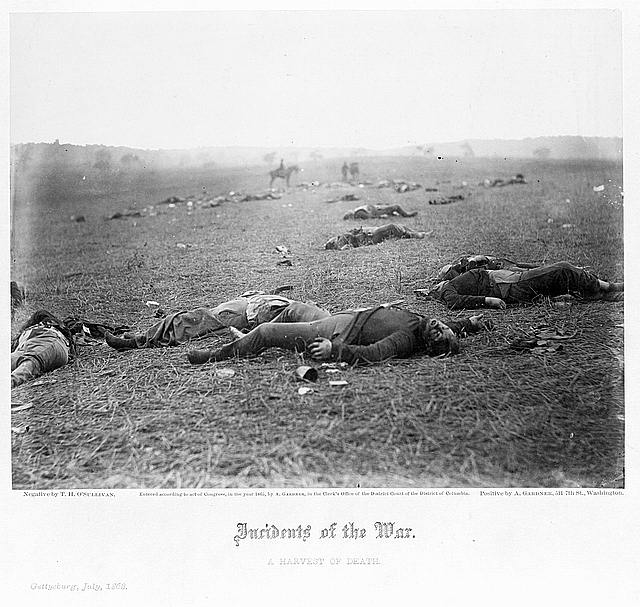

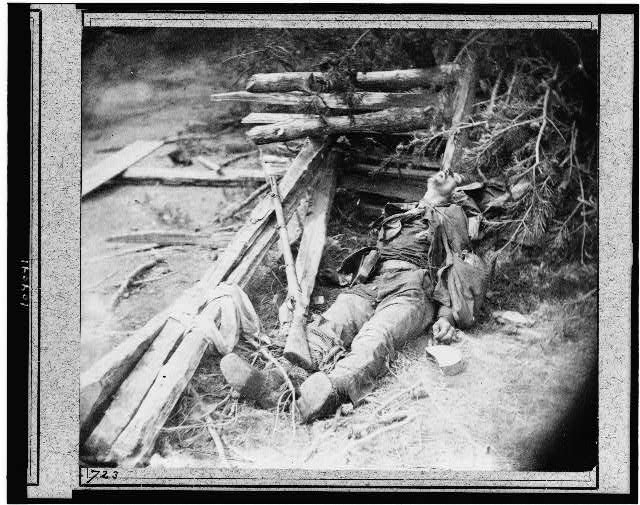

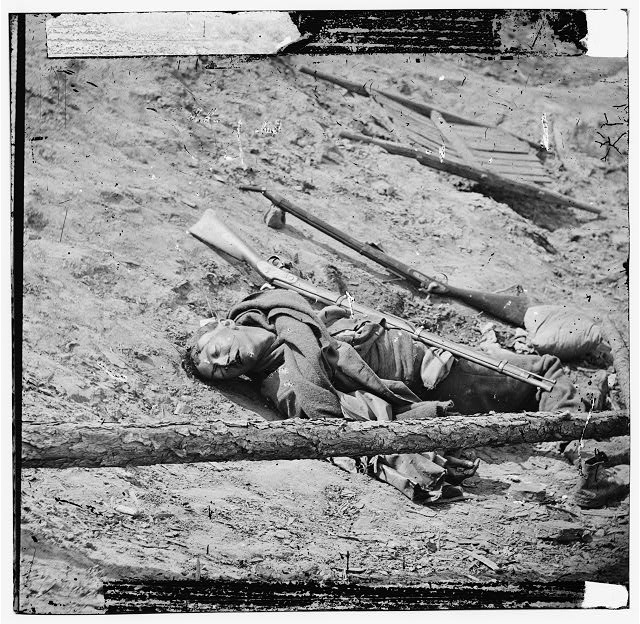

The more gruesome photographs showed what the illustrated newspapers did not. Renowned photographers such as Alexander Gardner, Matthew Brady, and Timothy H. O’Sullivan, as well as other anonymous photographers, did not shy away from capturing the lifeless bodies that lay across the tarnished American landscape. By the 1860s, photographic technology had developed beyond the daguerreotype, and included such forms as the albumen print, which was reproducible, and printed on paper. This evolution allowed for these kinds of photographs to be easily be shared. These images were displayed in exhibitions at a photographer’s gallery, printed in books, or included with the names of the dead in newspapers. The photographs became iconic. The reality of war was finally able to seen by civilians. It not only depicted the harsh reality of the cultural and political schism that was shaping the country, but it also humanized the war in a way that drawings simply could not. The photographs were clear and still, and the faces and bodies of the fallen soldiers represented all of the fallen brothers, fathers, and sons that America had lost.

These photographic depictions of fallen soldiers and their final resting places are documentation of the Civil War, but also serve as a kind of memorial object. The anonymous faces and bodies within the photographs are a testament to the service of every soldier who lost their life serving for their country. Despite the troubling nature of the images, these photographs literally mark the death of those who do not exist within the databases, lists, and cemeteries of the Civil War dead. In this way, these photographs represent the anonymous soldiers: they are given faces, and stories are given endings.

Many years later, these culturally significant photographs serve as only the beginning to a long standing tradition of war photography. In 2015, it’s impossible to imagine conflict without seeing photographs of it. The way that we imagine and talk about war is now inherently shaped by the images that are produced of it. In this way, we can see a particular version of war through the snap of a camera, on the front page of the paper, on the screens in our homes. These images serve as a reminder that history is inherently shaped by war, and those that died fighting in. Photographs of the dead show us that their loss of life was not in vain, but deeply impacts and shapes our communities, cultures, and landscapes to this day.

Order member Kelly Christian is a Chicago-based researcher, artist and staff writer for Dilettante Army Her most recent work explores postmortem and funerary photography. Kelly photographed military funerals in Maine during the height of the Iraq War and created her own new media-Daguerreotypes. She has presented her work at conferences and galleries across the country on postmortem photography, embalming, and “corpse-as-culture.”