True crime may seem to be having a moment right now, but illicit tales pulled from real life have long been at the forefront of popular culture. While today’s true crime fans might binge-watch a streaming serial killer docu-series, or go deep into the rabbit holes of Murderpedia, aficionados of previous centuries collected figurines of notorious criminals and bought pamphlets recounting the ghastly details of the latest villainy.

Staffordshire figures were all the rage in 19th-century England, where the brightly colored ceramic sculptures — recently made affordable by advances in mass production — regularly depicted contemporary celebrities. Queen Victoria riding a horse or Florence Nightingale tending to a wounded soldier could sit alongside miniatures of the singer Jenny Lind or Lady Franklin, wife of the leader of the doomed Franklin Expedition. Then there were the murderers.

An 1856 ceramic of William Palmer, aka “The Prince of Poisoners,” was fabricated the same year he was hanged in front of a crowd of 30,000; 1859 ceramics of Marie and Frederick George Manning were issued the year they were executed for murdering Marie’s lover Patrick O’Connor and burying him under the kitchen floor. Marie was portrayed dressed in a bonnet, holding a handkerchief; the sole indication of her identity was her name in gilt script on the earthenware object’s base. Often these crime-themed figures were “flatback,” meaning the reverse was flat, so they were cheaper to make and meant to be placed on a mantelpiece among other curios. Aside from rare exceptions — like an 1866 group showing Thoman Smith Junior and William Collier engaged in mortal combat — there was nothing overtly violent in their designs.

As Rosalind Crone writes in Violent Victorians: Popular entertainment in nineteenth-century London, “the new preoccupation with narratives of extreme interpersonal violence that emerged around 1820 ensured that murderers predominated within the criminal genre and meant that there were men and women eager to purchase them for display within their homes.”

Staffordshire factories were not the only ones manufacturing Victorian crime knickknacks. The 1899 Catalogue of a Collection of Pottery and Porcelain Illustrating Popular British History from the Victoria and Albert Museum has an entire section on crime, including a creamware mug with a portrait of murderer John Thurtell and another with George Barrington, the “Gentleman Pickpocket.” Yet the Staffordshire factories were particularly prolific in producing ceramics at exactly the moment when public obsession with a crime was at its height. For instance, multiple variations exist of the sites and figures related to murderer James Blomfield Rush, indicating how these factories were rushing to meet demand.

In 1848, Rush killed his landlord Isaac Jermy and Jermy’s son, with Staffordshire creating not just a figure of Rush with his hand on a podium and a document in the other (perhaps referring to his disastrous self-defense at his trial), but a whole diorama of the crime. This included models of Rush’s home, Potash Farm; the murder site, Stanfield Hall; and Norwich Castle, the location of Rush’s hanging in front of thousands of onlookers. There had been a similar treatment for the 1827 “Red Barn Murder,” in which farmer William Corder shot Maria Marten, who he’d asked to meet at the barn ahead of their planned marriage. The 1828 Staffordshire models showed Corder and Marten together in a pose that could be mistaken for idyllic lovers, as well as the infamous red barn itself. In one version, Corder stands in the open door, inviting Marten to join him inside. The actual barn in Suffolk was ripped apart by thousands of souvenir seekers.

While murder memorabilia was in a frenzy in 19th-century England, these figures were also a visual portal into the crimes at a time when illiteracy was high. Myrna Schkolne, author of the 2006 People, Passions, Pastimes, and Pleasures: Staffordshire Figures, 1810-1835, told Collectors Weekly that the earliest example of a ceramic murder souvenir is likely one of French Revolution leader Jean-Paul Marat killed by Charlotte Corday. “But it wasn’t until 1810 that inexpensive prints showing everyday things became widely available, and that also affected Staffordshire figures,” Schkolne explains. “Broadsides, or penny strips of newspaper depicting events of the day, were often made from cheap woodcut engravings and sold on street corners.”

The poisoners and bludgeoners sculpted with rosy cheeks were a new way to transmit these stories in the 19th century, yet they followed a long history of such wares. Murder pamphlets that related prominent crimes to a popular audience had already been popular for centuries. They started as single broadside sheets and expanded into small books with innovations in publishing. As J. A. Sharpe writes in Past & Present journal: “Ever since the popular press had been established in England, much of its output had been devoted to crime, its major concern being the sensational and newsworthy case: from the start the purveyors of popular literature were convinced, as a Victorian ballad-seller was to claim, that ‘there’s nothing beats a stunning good murder.’”

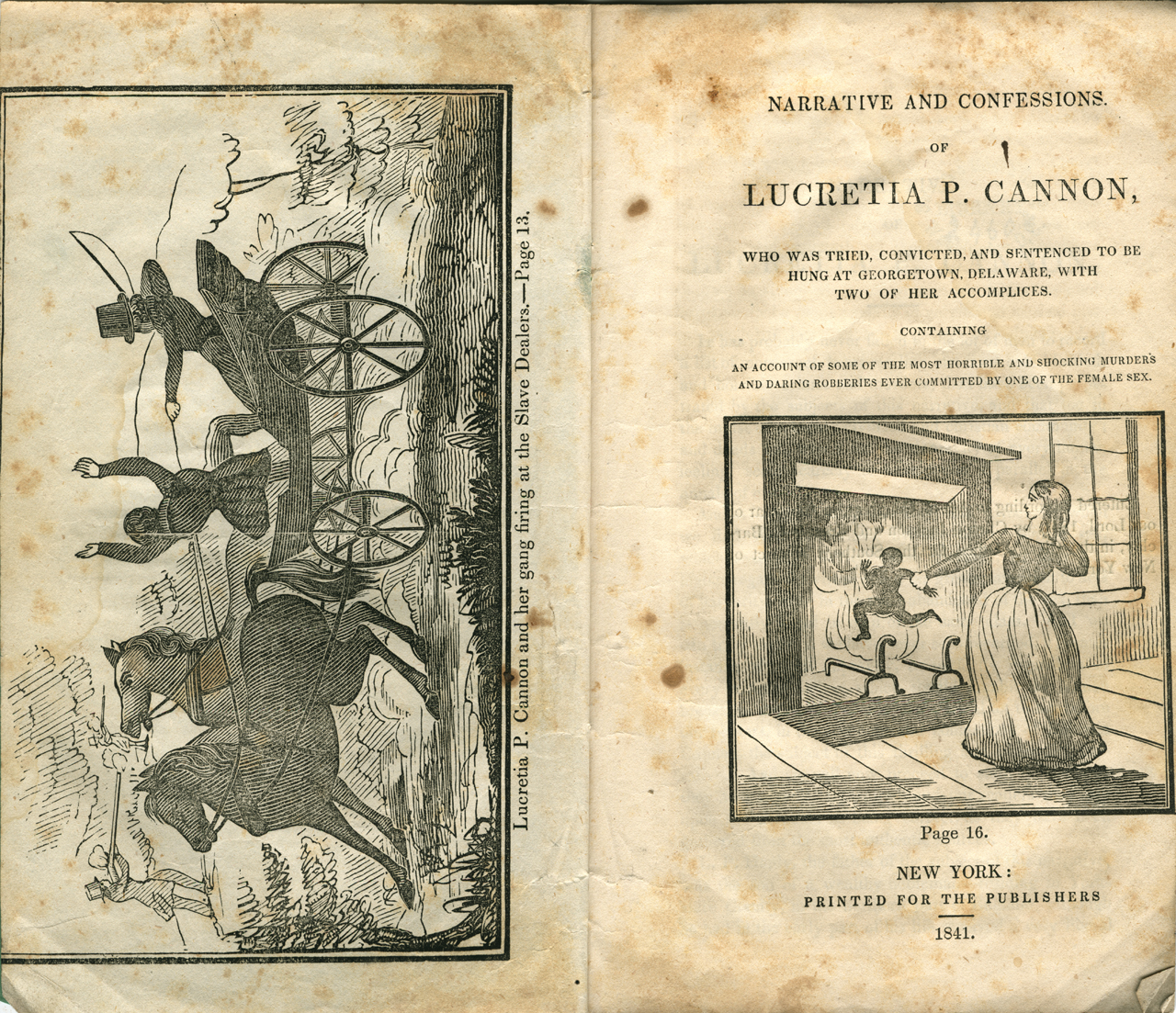

These pamphlets spread to the United States. Sometimes they were sold to spectators at an execution, although more frequently they were hawked in town squares and taverns for the many who could not make it to the event. They printed the perpetrator’s confession, proceedings of the trial, and graphic narratives of the crime. Many were illustrated. These engravings featured portraits of the murderer and their victim or victims, the locations of the crime, diagrams of the weapons, and even the act of the crime itself. These were not journalistic affairs, with publishers competing to get theirs out first with the most dramatic details.

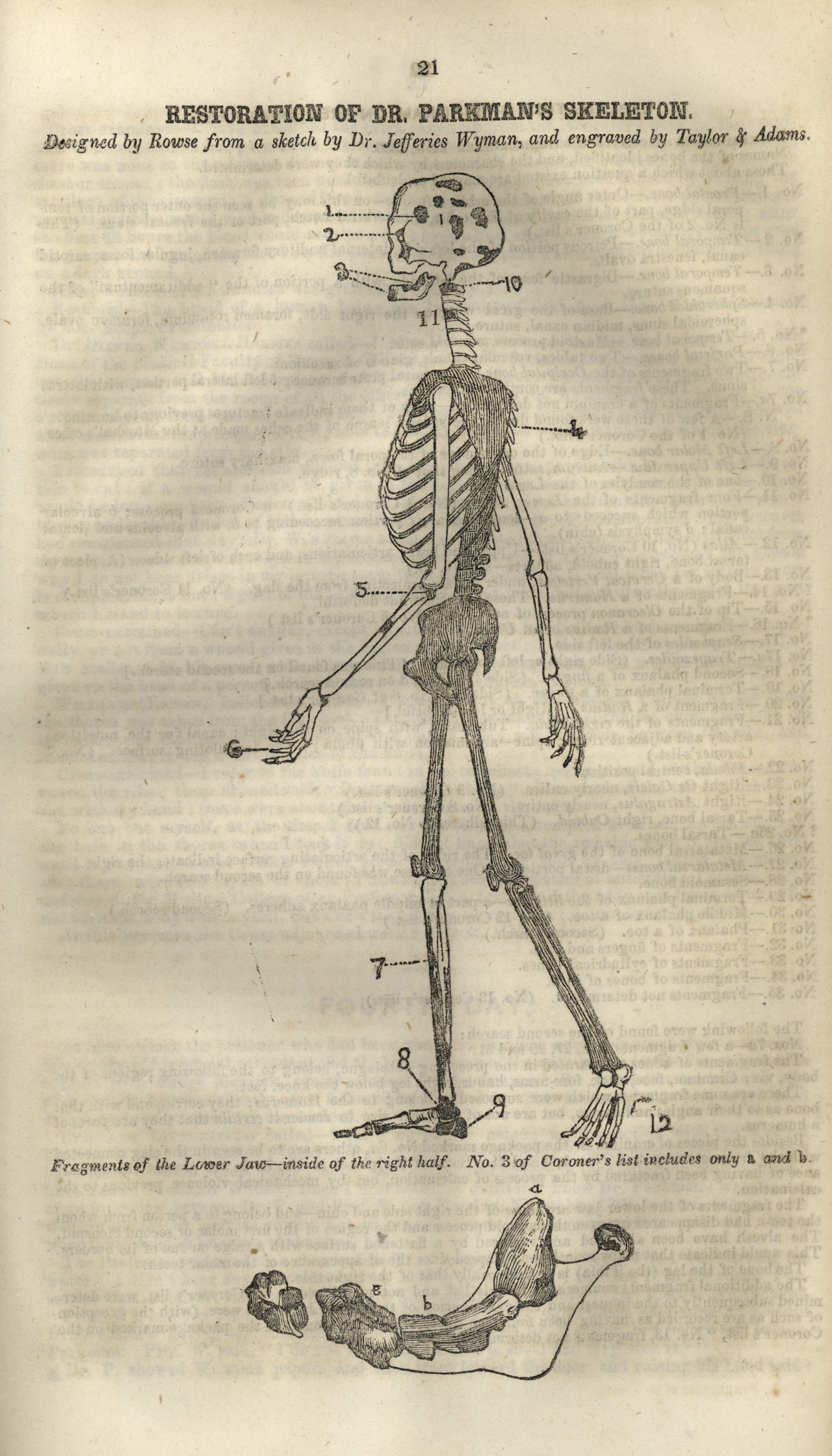

The US National Library of Medicine has an online archive of these pamphlets. One for the 1830 trial of John Francis Knapp, accused of hiring a man to murder his uncle, included an illustration of the bludgeon “loaded with lead” used to carry out the deed, while the 1845 pamphlet on the trial of Abner Baker for murdering his brother-in-law begins with an elaborate map of the jail and courthouse. An especially popular subject was the 1849 murder of Dr. George Parkman. These relayed all the gruesome details of his death, such as the dismembered body parts found at the dissecting laboratory of Dr. John Webster which led to his hanging for the crime. Pamphlets illustrated the decayed remains, the restoration of Parkman’s skeleton from the severed parts, and Webster’s prison cell.

By the 20th century, these pamphlets were replaced with cheap paperbacks which continued to disseminate methodical chronicles of crime. With each new evolution of media, crime has always crept in with its secondhand thrills. Although there are ethical questions about how murder is so quickly turned into entertainment, it is a reflection of how these safe brushes with mortality — when everyday life can be disrupted by horror — remain a source of lurid fascination.