The spring of 1847 brought stormier skies than usual to Ireland. Hordes of desperate people filled ships said to be tight as coffins. It was a final attempt to outrun starvation at the hands of a bigoted government. They would never see Ireland again, but they might survive…

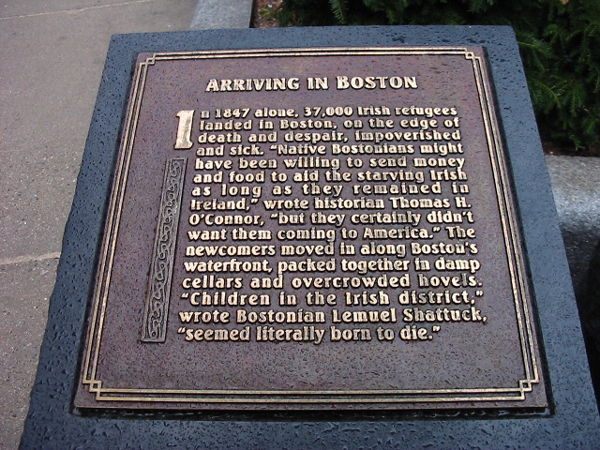

In Boston, MA, USA, citizens saw only threats to their mortality. The Coffin Ships emptied their bodies onto Long Wharf — some did not move, others ambled into the nearest shelters. They were gaunt, filthy, covered in sores, burning, contagious —the walking dead.

Faced with this tangible vision of death, Boston’s ruling class doubled down on long held prejudices against the Irish. A Protestant-leaning bias against Irish Catholics became fear of a Holy Roman takeover. A letter to City Hall predicted, “…we shall be driven from our homes by the Lazy, Ungrateful, Lying and Thieving population of old Ireland.” (sic)

But the paranoia on Beacon Hill was not some communal madness. The reaction from Boston’s upper class is defined by psychologists as Terror Management Theory (TMT). Faced with an assumed threat, the brain associates familiarity with safety. It’s the same instinct that causes a fear of strangers. But this psychological defense can also lead to denial of evidence. It can even influence politics.

With one panicked vote, city councilmen designated Deer Island, five miles into Boston Harbor, as the “… suitable and proper place to attend to all the nuisance and sickness accompanying navigation…” It was a reactionary decision that ultimately cost hundreds of lives and robbed thousands more of their humanity.

With one panicked vote, city councilmen designated Deer Island, five miles into Boston Harbor, as the “… suitable and proper place to attend to all the nuisance and sickness accompanying navigation…” It was a reactionary decision that ultimately cost hundreds of lives and robbed thousands more of their humanity.

On Deer Island, a building was hastily erected and a single doctor was designated to screen incoming ships. By summer, the Deer Island Hospital was quarantining 400 new patients per week, most of them young, at 14 to 20 years old. The ills they suffered; typhus, scurvy, even the high birth rate, were symptoms of starvation and poverty. The immigrant mortality rate could have been drastically impacted by expansion of charitable services on the mainland. Yet Bostonians marveled, as if the pain were self-inflicted. Councilman Lemuel Shattuck declared, “…they seem literally born to die.” Every possible diagnosis was used to keep a person on the island. Records described the refugees as mostly suffering “fever,” a symptom too general to justify quarantine, let alone internment.

For three years, thousands of Irish refugees were confined to Deer Island for indefinite sentences. One doctor was given the impossible task of managing them all. The single room filled with cots end to end stank with diarrhea. Cramped and communicable, Deer Island would claim 800 to 1,200 deaths. They survived the brutal Atlantic crossing, then succumbed to fate within clear sight of freedom. A last, their bodies were dumped in anonymous mass graves.

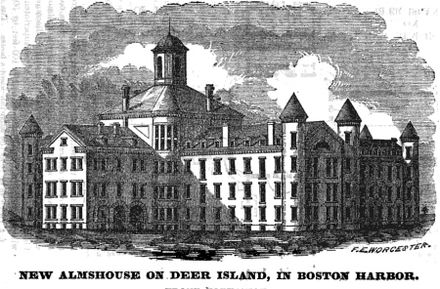

Two additional buildings were constructed on Deer Island in 1850. These served as the foundations of an almshouse and a prison that would operate for another two decades. The use of Deer Island morphed from internment for the Irish, to a vague separation of any poor and unworthy from the rest of the city. Whether out of trauma of the victims, or guilt of the perpetrators, Deer Island Hospital fell out of public awareness.

In 1990 construction began at Deer Island for an innovative new water treatment facility. Work came to halt, however, when backhoes unearthed a cache of human remains. Expecting the remains to be Native American, city coroners were shocked when DNA testing identified the bones as Irish. The archival work began to exhume the memory of the Deer Island Hospital.

Finally, on May 25, 2019, a 16 foot Celtic cross of Irish granite was dedicated to those forgotten souls. Mayor Marty Walsh and other officials spoke to over 600 members of the Boston Irish Community. The monument serves not solely as a memorial, but as a warning.

Our TMT (Terror Management Theory) response is both a feature and a flaw of human evolution. The fear of death kept our distant ancestors safe when resources were limited to hunting and gathering, but today it disguises unarmed black men as aggressors, or slanders those without the language to defend themselves. Confronting the fear of death frees the mind to be critically aware of facts. The age and statistics of the Deer Island refugees mirror those of refugees around the world today. Most are young people who have braved the most dangerous natural conditions to escape the most dangerous man made conditions; war, famine, persecution. Anti-immigration arguments invoke a TMT response with unfounded images of shortage and violence. Narrow understanding leads to policies that serve to punish those who suffer simply for having suffered. Fear does not wait for evidence.

This fear-based status quo often results in internment of thousands of displaced people, unable to move forward or back. Bigoted policies, oftentimes purposefully cruel, rip families apart and cause permanent psychological damage. Overcrowding, unhealthy rations, draconian deprivation mental and physical stimulus are the standards of detainment. For the first time in over a century, refugee children have died in US custody.

The spirits of Deer Island tell the truth of all refugees. They had been given one choice in Ireland: leave, and maybe live — or stay and die. When a person walks 1,700 miles, or sails into dangerous waters, it’s because they are faced with this same choice: leave, and maybe live — or stay and die. The rest of us have another choice. We can choose to question the sources of fear. We can choose to help those in need.