“Grief is different. Grief has no distance. Grief comes in waves, paroxysms, sudden apprehensions that weaken the knees and blind the eyes and obliterate the dailiness of life.”

Joan Didion, The Year of Magical Thinking

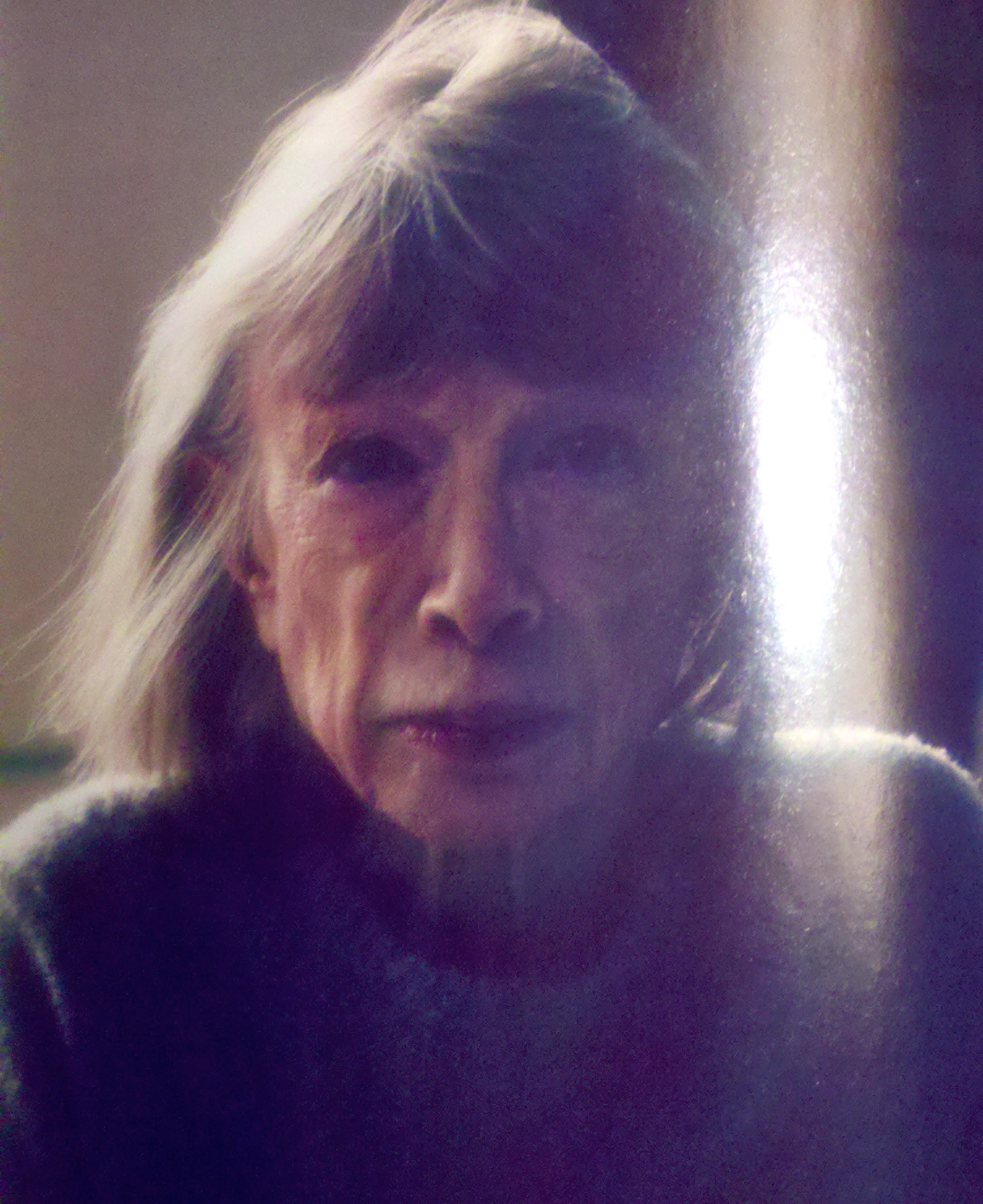

This is a picture of Joan Didion from this month’s Vanity Fair. Look at her face. Doesn’t it seem like the face of a woman who has lost her whole universe in untimely and tragic ways?

Didion wrote The Year of Magical Thinking after the death of her husband from a sudden heart attack. Now she has written Blue Nights about the death of her only daughter just two years later.

This June I was sitting alone at a coffee shop in Chicago, waiting for a friend and reading The Year of Magical Thinking. The barista commented on it when she brought over my fancy hand pressed cup of coffee. She was young, perhaps not even thirty, blond. I told her that I was a mortician, so people had been telling me to read this seminal book on grief for years. The barista, suddenly enthused, started with some pretty standard questions, “do you put makeup on the bodies?” and “did you have to go to school for that?” Then, as if testing the waters, she told me that the book had been sitting on her bedside table for months. People had been telling her to read it for years as well. “Really, why?,” I asked. “Well, two years ago my fiance and his best friend were murdered.”

People talk to me about death. Not just at work. On the airplanes, parties, at coffee shops.

The barista widow told me that for months and months she would go from therapist to therapist, hoping someone would help her with her grief. Someone to explain to her why she felt like she was going crazy. Some therapists went as far as to tell her there was nothing they could do for her. Nothing they could do for her. As if grief is a fatal disease or a sold out Xbox 360 game.

When I walk into a home to deliver an urn, I will often ask the person, the griever, how they are doing. Sometimes their answer is simply, “hanging in there.” I don’t press them. But more often than not the response is like a floodgate bursting. Like the woman who was sure that her husband hadn’t really been dead when she called the funeral home, and she had killed him by having him taken away. Or the son who walked in to find his father hanging from the rafters and lied to his sister in South Carolina about it being a natural death.

I mean it when I say that you would not believe the things I’ve heard. Stories I would not repeat, not because they are too violent or painful, but because they would seem ludicrous. You would think I was making them up.

No matter what the tale of woe, horrific or simple, all you can do is listen. You can’t fix anything at that moment, when it seems like nothing will be fixable ever again.

Psychologists have insisted that euphemisms for death are poison. Yet we cannot help ourselves from lobbing softballs at grieving people like, “he is in a better place” and “he’s sleeping with the angels” and “he doesn’t suffer anymore now that he’s passed on.” When the truth is that he’s finally begun to decompose after dying from an illness with more suffering than a human body should ever be required to experience. And yet here someone tells you, grieving widow, that they, “know how you feel, but he’s happy now.” No, you DON’T know how I feel you stupid bloated cow. Grief gnaws at the lining of my heart like a small, rabid rodent and it feels like no other person has ever felt anything so hideously grotesque before in the history of human emotion. Unless you too have recently stared into the black void of hopeless emptiness and heard your scream echo back at you than no- NO, you do not know how I feel. Good day to you, sir.

Euphemisms are like putting a cartoon children’s band aid on a gaping wound that requires stitches or surgery. Perhaps it makes you feel better, like you’re doing or offering something, but it does not help. The best thing you can say is nothing. I don’t mean say nothing as in, stay silent and pretend it didn’t happen. I mean you ask a simple question and then listen. Or, “I’m sorry, that’s awful, I can’t imagine.” Because you can’t.

I’ve spoken to someone about death every single day of my life for three and a half years. I don’t get tired of it. True, it makes me more desperate than I’d like sometimes. Desperate to love, interact, move on it now. More than other people or the normal pace of life wants to allow. But every day is unique cocktail of passion and honor and humor and despair. A life worth its weight in corpses.

Vive la muerte!

Your Mortician