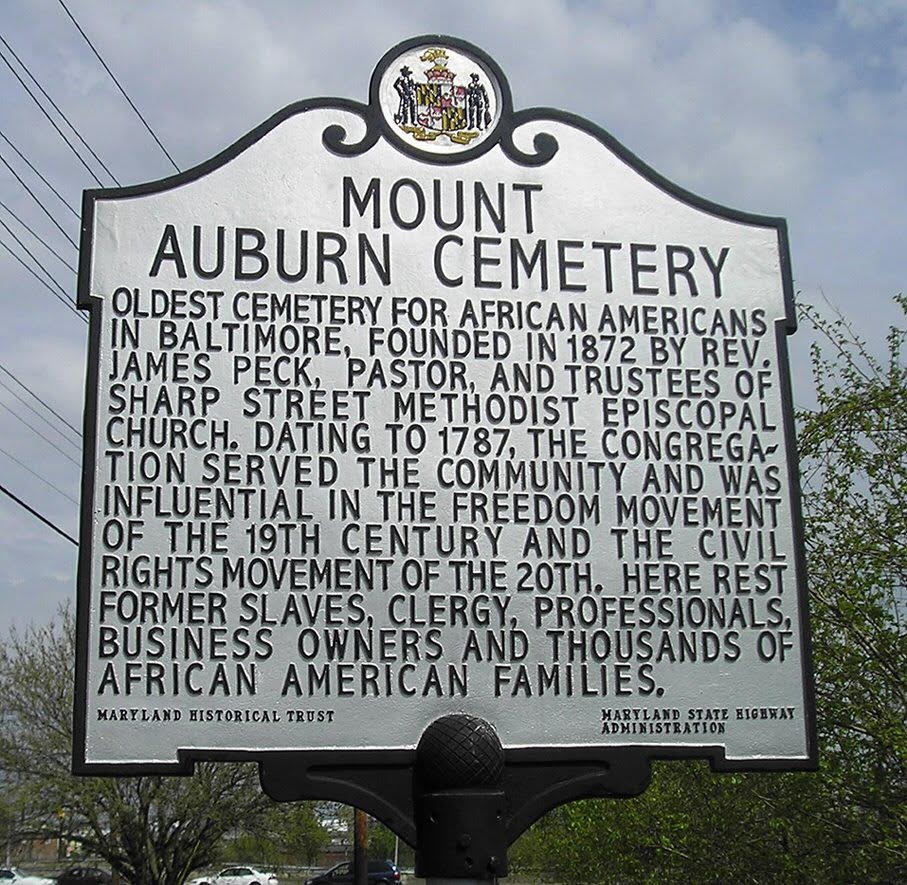

Did you read the historical marker in the opening picture? Go back and read it, carefully and completely. Let the words oldest cemetery for African Americans…served the community…influential in the freedom movement of the 19th century…here rests former slaves and thousands of African American families…just wash over you.

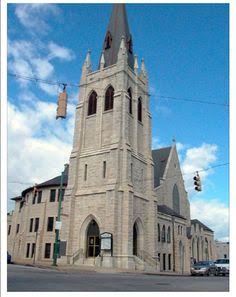

Mount Auburn Cemetery was all of this. It stands, as the marker so clearly illustrates, as a site of memory for the struggle and progress of African Americans within a hostile white supremacist society that normalized enslavement and the dehumanization of Black bodies. As the historical marker states, it was founded by the oldest Black United Methodist Church in Baltimore making Mount Auburn an autonomous space for Blacks to receive a proper and decent burial at a time when those of African descent were legally labeled the property of white merchants and planters.

As beautifully powerful as is the placard, it does not even begin to tell the full origin story of the historical treasure trove. The history of Mount Auburn did not start in 1872. And what’s more is that it would not be until the Trustee Board meeting of June 30, 1903 before it would be officially renamed Mount Auburn Cemetery. In fact, what is unbeknownst to many is that the cemetery (and its current location) is the last phase of a burial ground that was first established in Baltimore in 1807 – the culmination of three early grave yards established by Sharp Street Memorial United Methodist Church. The African Burying Ground (the first phase) was established in what was then Baltimore county. The city later expanded to include the cemetery making its geographical location South Baltimore. By 1839, the African Burying Ground filled up and new land, again outside the city limits, was purchased. Belair Burial Ground, as it was now called, interred people until 1870 when a major expansion plan was underway to again disinter everyone from Belair Burial Ground to the new Sharp Street Cemetery located in South Baltimore, where it started. All of this, its founding and geographical moves around Baltimore, directly paralleled the experience of Black people in Baltimore.

The African Burying Ground was founded as the simultaneous call for freedom and humanity as well as a call for actualized burial rights for Black people and people of color. Black men and women lived enslaved and comprehensively oppressed but fought to establish an autonomous piece of land that would carry and display Black humanity and Black freedom in the afterlife. When the seven trustees of the African Methodist Church (now Sharp Street Memorial United Methodist Church) took up this charge only five years after financing a brick and mortar church it was important they established a grave yard that would be 1) designated for Black decedents and decedents of colour; and 2) remain Black-owned. This is clearly illustrated by the language of the June 1807 deed between Francis Hollingsworth (the white merchant and devout Methodist from whom the land was purchased) where it plainly stated that the land was to “serve as a burying ground for the Africans or people of colour of the precincts and the city of belonging to and in communion with the society of Christians.” What’s more, is that when those seven trustees cease to no longer serve in the capacity, the burial ground was not to revert back to the umbrella United Methodist Church (read white) but was to be passed down to the next set of trustees. This may sound like common sense but during an era of institutionalized slavery where to be Black and a slave were legally synonymous, land owned by Blacks where funerals of all those of African descent were protected, normalized, and respected and up-to-date burial and death records were kept (this early in the nineteenth century) was not to be assumed but met with shock!

The African Burying Ground was founded as the simultaneous call for freedom and humanity as well as a call for actualized burial rights for Black people and people of color. Black men and women lived enslaved and comprehensively oppressed but fought to establish an autonomous piece of land that would carry and display Black humanity and Black freedom in the afterlife. When the seven trustees of the African Methodist Church (now Sharp Street Memorial United Methodist Church) took up this charge only five years after financing a brick and mortar church it was important they established a grave yard that would be 1) designated for Black decedents and decedents of colour; and 2) remain Black-owned. This is clearly illustrated by the language of the June 1807 deed between Francis Hollingsworth (the white merchant and devout Methodist from whom the land was purchased) where it plainly stated that the land was to “serve as a burying ground for the Africans or people of colour of the precincts and the city of belonging to and in communion with the society of Christians.” What’s more, is that when those seven trustees cease to no longer serve in the capacity, the burial ground was not to revert back to the umbrella United Methodist Church (read white) but was to be passed down to the next set of trustees. This may sound like common sense but during an era of institutionalized slavery where to be Black and a slave were legally synonymous, land owned by Blacks where funerals of all those of African descent were protected, normalized, and respected and up-to-date burial and death records were kept (this early in the nineteenth century) was not to be assumed but met with shock!

In 1664, only 30 years after the English settled in what they called Maryland, an Act Concerning Negroes & Other Slaves adopted that all Black persons living, coming to, and born in Maryland were slaves Durante Vita (Latin for “during life”). Compounded with the fact that your life was now not your own, the 1701 Act for the Establishment of Religious Worship solidified that every enslaved Black woman, man, and child met death as a slave. The act legalized the omission of “Negroes and Mulatoes” from county government burial registers using racism to deny blacks and people of color Christian freedom. In this way, race was used to construct a thick border privileging whites to burial rights while denying them to Blacks and people of colour.

Then, as it is now, burial’s the ceremonial act of sending the decedent to the afterlife. Through song, dance, food, and remembering the life of the deceased, the funeral’s the bridge between life and the afterlife. And for enslaved Blacks of the colonial era, this bridge was the walkway to FREEDOM! What must be made clear, but is often overlooked, is that funerals and obsequies are about self-actualized liberty.

The African Burying Ground became the realized part of that freedom – it was a 2 ¼ acres tangible geographical location where black life mattered. Prior to its founding in 1807, Marylanders of African descent were largely buried in the Potter’s Fields, so-called “slave cemeteries” or one of three Catholic grave yards. [1] Potter’s Fields, a grave yard where the unclaimed dead were interred four to a lot, was established in Baltimore in or around 1796.

Decedents were numbered, unprotected, and forgotten. With the threat of body snatchers spurred by the need for cadavers at local medical colleges, the dead were never really laid to rest in Potter’s Fields.[2] Slave cemeteries – separated patches on slaveholders’ land meant to denote racial and social otherness where enslaved persons were buried in bondage – was a complete affront to freedom. It is important to understand that the freedom through death enslaved Blacks sought was as real to them as the life of slavery and oppression they lived. Records and scholars attested that bond women and men believed death to symbolize freedom. How then could freedom from enslavement happen when a body was buried on slave land?

The body may have been buried on slaveholders’ land but according to African American death ideology (the ideas that enslaved Africans expressed about the belief in their soul’s freedom in the afterlife) the conclusion is clear – the soul was set free at death. In her most recent work, The Price for Their Pound of Flesh, Daina Berry discussed the soul in terms of the most fiercely protected, coveted secret and unquantifiable value of African Americans that slaveholders could never take. These “soul values” she said developed during the adolescent and young adult years through “inner spiritual centering that facilitated survival [and] were reinforced by loved ones.” Berry described “soul values” as “a spirit, a voice, a vision, a premonition, a sermon, an ancestor, (a) God”. It was this high value placed on the soul that continued the importance of burial and burial place for African Americans and their descendants.

Once established, the African Burying Ground was a safe haven for enslaved and free Blacks. In 1818, 105 Black persons were recorded buried in Baltimore. To put this in context, 574 Black people died that year and of that number: 211 went to Potter’s Fields East and 184 went to Potter’s Field’s West while only 20 were buried in the three Catholic grave yards, 2 in the two Baptist church grave yards, and 1 in the Episcopalian grave yard. What this means is that 105 or nearly 30% of souls were saved from the Potter’s Fields and that outside of the African Burying Ground, there was not a real option for Black people to have a proper burial.

Belair Burial Ground, the second phase, was active from 1839 until 1878 when the Baltimore City Street Commissioners chose to extend Patterson Park to North Avenue. At this point, Sharp Street Church decided to disinter and reinter all 475 bodies across northern Baltimore county lines down to the southern half of Baltimore city to an 8-acre burial plot deeded seven years earlier in December 1871. This was a magnanimous undertaking [pun intended] that with twenty hired hands took the church three full months and cost $5,285.97 – roughly $131,000 in today’s currency! The move put what was now called Sharp Street Cemetery back in south Baltimore for good.

Spearheading the move from start to finish was perhaps the church’s Christian duty and some may even argue that since it was no fault of the lot holders, the responsibility indeed befell Sharp Street Church to again lay each soul to rest. But what must be pointed out is the notion of self-help and racial uplift that was clearly at the helm. Preached as a philosophy by easily the most influential African American of the late 19th/early 20th century, Booker T. Washington, self-help became a mantra after the Freedmen’s Bureau went bankrupt and the federal government pulled out the south leaving former slaveholders in charge of law and policy and Black folks to, once again, fend for themselves. Self-help was the idea that since help was not coming, Black folks must help themselves.

Following the Reconstruction Era (1865-1877) was a time of legalized national oppression and subjugation which normalized customs that discriminated and subjugated African Americans in their day-to-day lives. Many cemeteries had a “Black section” or enforced de facto policies that only welcomed white lot holders. Sharp Street Cemetery, then, developed as a 26-acre geographical space where African Americans were not just welcomed but venerated post mortem. Sections of the cemetery were named after well-known Baltimore undertakers such as William Dungee, John Toadvin, and Hercules Ross. Walkways between each section were named after prominent African Americans – Brown Avenue for Rev. Benjamin Brown, Sr. the first African American preacher of Sharp Street Church and first preacher seated in the law-making body of Methodism in the history of the Methodist Episcopal Church; and Young Avenue for Jacob Young, African American preacher who petitioned the right to form the Washington Conference, first session for the Colored Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church.

In 1904, a year after the cemetery was named Mount Auburn Cemetery, church trustees ran monthly ads in the Afro American newspaper advertising their newly renovated cemetery as “one of the most beautiful cemeteries in the state that our people have access to [emphasis added]”. This was a direct attack against Jim Crow segregation. The inclusion of the phrase “our people” let African American know that they are fully welcome to a perpetually cared, first-rate cemetery with a serene river view while it simultaneously informed white Americans that Black folks did not need (or want) their “Black sections” and were unbothered by their whites only covenants.

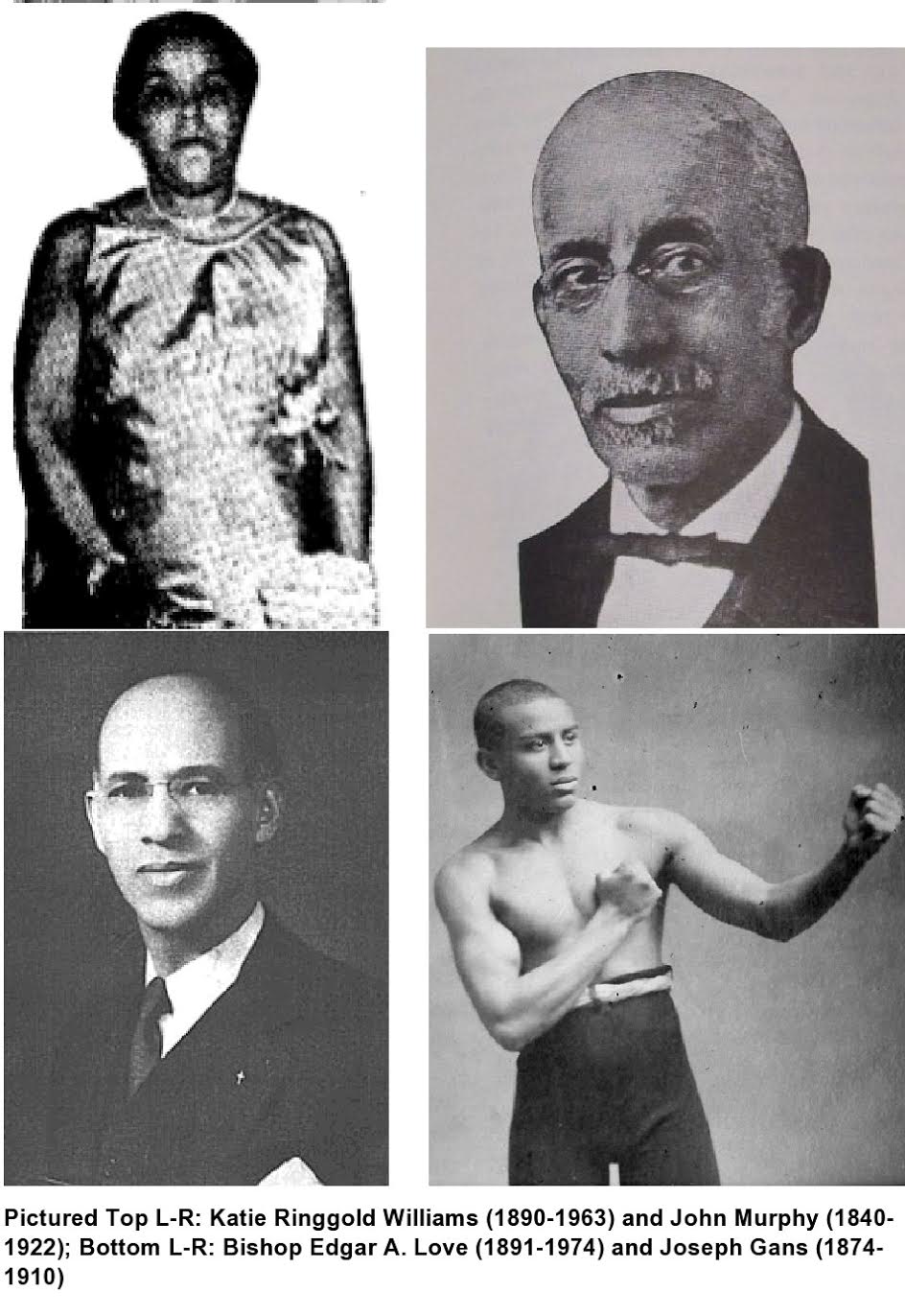

Today, as 34-acre Mount Auburn Cemetery located back in south Baltimore, the cemetery proudly stands as a living memorial of Black history. And not just symbolically speaking. No. Deep under its surface within the soil for tomorrow’s life is 211 year-old Black Baltimore history. From enslaved Africans to the Who’s Who of Baltimore are buried within its keep – Baltimore’s first independently licensed Black female mortician (Katie Williams), Maryland’s first Black female licensed to practice medicine (Dr. Nellie Young) and founder of the Afro-American newspaper (John Murphy) to name a few. Mount Auburn Cemetery is also the keeper of national heroes, such as Joseph Gans, first African American Light-Weight boxing champion as well as those with national acclaim such as Bishop Edgar A. Love, founder of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc.

Mount Auburn Cemetery is a historical landmark two times over – in 1986 designated a Baltimore City Landmark and in 2001 entered in the National Register of 2001. It stands as a testament to a fight won for burial rights for Africans and people of colour. It illustrates the prominence of Black history and heritage on which Baltimore was built.

Please note: This piece is based on an essay to be published as part of a forthcoming anthology. See Kami Fletcher. “ ‘Negroes and Mulatoes Excepted”: How Early Maryland Law, Protected Burial Borders, and Slave Cemeteries Shaped Burial Rights for Blacks.” In Til Death Do Us Part: American Ethnic Cemeteries as Borders Uncrossed Edited by Kami Fletcher and Allan Amanik by University Press of Mississippi (2019 projected date).

Footnotes:

[1] “Slave cemeteries” – every plantation that held African/African Americans captive did not set aside land for “slave cemeteries.” Some used headstones to serve as a demarcation line while others simply did not have one at all leaving burial and all obsequies to the slave community. Regardless, research shows that enslaved women and men inverted the lens of death and used what Diane Jones called the “African American landscape” to bury loved ones far away from slaveholders and close to slave quarters and/or near edges of the property (out of sight) for spiritual protection from the slaveholders. See: Diane Jones, “The City of the Dead: The Place of Cultural Identity and Environmental Sustainability in the African-American Cemetery,” Landscape Journal 30 (2011). || Catholic cemeteries – Between 1793 and 1800, forty-three “free mulattos,” “children of color,” “French negroes,” negroes,” “negro slaves,” and “free negroes” were buried in St. John’s, St. Peter’s or St. Patrick’s burying grounds in Baltimore, MD.

[2] “Accused of Body Snatching,” Baltimore Sun, February 19, 1898.