From 1985 to 1987 I was a Peace Corps volunteer in Togo, West Africa. I lived in a small village in the hot, dry, sub-Saharan north. My next-door neighbor was Adia, a 30-something man with a round face and a ready smile.

One morning, his maternal grandmother died quite unexpectedly. She was probably about 80, judging from the ages of her children and grandchildren, though most everyone you asked, including Adia, said she was over 100. It made me wonder about all the other folks who claimed to be 100.

Adia asked if I would drive him to the nearest town on my motorcycle to telephone his brothers. En route, we stopped at his grandmother’s house to check on things. Of all the close relations present, Adia was the senior male, and thus responsible for logistical details and organization. He lived for this stuff. Datebook in hand, he made a quick reconnaissance, as if he were the general checking in at headquarters.

The old woman lived in a small mud hut. The round, thatch-roofed dwelling was perched on a terrace below some cliffs, with a sweeping view of a boulder-strewn slope, and a valley below. Clouds lent depth to the sky. The air was still and warm.

The old woman lived in a small mud hut. The round, thatch-roofed dwelling was perched on a terrace below some cliffs, with a sweeping view of a boulder-strewn slope, and a valley below. Clouds lent depth to the sky. The air was still and warm.

Several older women bustled about, quietly cleaning and arranging the house and yard. The grandmother lay on her sleeping mat in the small, round room. A granary in the center kept the harvest safe from thieves and animals. The old woman was curled on her side, covered with a cloth, facing the wall. I expected to see her breath rise any moment.

We went to town, telephoned Adia’s brothers, then hurried back to his grandmother’s house. By now there were several dozen people milling around in the yard. Groups of old men were installed in quiet clusters in the shade. I couldn’t help wonder if they were dwelling more than usual on their own impending mortality.

Adia’s mother, “mama,” was there, and I went in to say hello. Her mother’s body had been moved to a mattress on a metal bed frame. Around it was a cluster of wailing women. Mama had swollen eyes and a very sad face. I gave her a hug, not knowing what else to do, and because it felt right, but I have no idea if it was appropriate.

Adia’s older brother had said he wouldn’t be able to come, but late in the afternoon his forest green sedan lumbered up to the gate. The faint sound of drums and wailing women echoed across the valley.

In such a hot climate, the body needed to be buried quickly. Near sunset, I put on my “village best” and went to watch the burial procession. The old woman had been wrapped in several layers of cloth, then lashed to four long wooden poles. Two young men carried her high above their heads, bouncing and swaying. Someone twirled a black parasol. The death of an old person is supposed to be cause for celebration, so the mood on the surface was festive. A throng of celebrants, well-plied with the local millet beer, was singing, dancing, whooping, and laughing.

The cemetery was a jumble of clay jars marking traditional graves, and several western-style, cement graves. I was told that only a few people knew how to dig a traditional grave–an egg-shaped hole about four feet deep, with a small access hole at the top.

As the crowd moved toward the grave, the carriers occasionally stopped and lowered the body to the ground. The crowd gathered around tightly, chanting loudly. I was told the body was being “hidden” from evil spirits.

We arrived at the grave site and the body was promenaded several times around the hole. The crowd, clumsy and aggressive with drink, pressed in closely. The bier was lowered to the ground. Amid much pushing and shoving by the crowd, the layers of cloth were removed one by one and handed to several women. The body was left in a thin white wrapping that gaped open in front. It was laced loosely, to prevent it falling off completely.

An old man stood in the hole, his head and shoulders above ground. The old woman’s body was lowered feet first into his arms and then into the hole. I’d never seen a dead body before, but unlike a white person, who I imagined would be a ghostly shade of pale blue, the old woman remained a healthy chocolate brown. Her body was limp. I was told she had been washed four times. Her nostrils were plugged with cotton from the kapok tree. Her eyes were closed, and her mouth hung open, her jaw slack. Her lips were the only bluish skin.

An old man stood in the hole, his head and shoulders above ground. The old woman’s body was lowered feet first into his arms and then into the hole. I’d never seen a dead body before, but unlike a white person, who I imagined would be a ghostly shade of pale blue, the old woman remained a healthy chocolate brown. Her body was limp. I was told she had been washed four times. Her nostrils were plugged with cotton from the kapok tree. Her eyes were closed, and her mouth hung open, her jaw slack. Her lips were the only bluish skin.

Once in the hole, she was curled in a fetal position, her hands under her head. A woman’s task is to prepare the evening meal after the family has worked all day, so she is buried facing the sunset. A man is buried facing the sunrise, as he must rise early each morning to work in his fields.

The old man climbed out of the hole and one of the old woman’s male relatives climbed in to make sure she was properly positioned. None of her children were allowed to be present, in this case because she had had twins. I don’t know if children were always barred from their parents’ burials, but in the case of twins, there were many special rules.

I was told that in the old days the body was covered with a layer of sticks. The opening was then closed with a round, flat rock. The dirt from the hole was piled on top, and an inverted clay jar was placed on the mound. If a young child in the family died, the grave could be opened, the sticks moved, and the child placed next to the elder, to be looked after and cared for. Our landlord said that several children were buried this way in his grandmother’s grave, but that this time-consuming and laborious process had become less common.

Once the old woman was positioned, two young men with short-handled hoes stepped forward and began scooping in dirt. As the hole filled, they tamped the dirt with sticks and rocks. Some quarreling began among the old men, and the crowd started to drift away. One of the old woman’s twenty-something granddaughters stood next to me, wide-eyed, and gasped, “My god, they’re juming up and down on my grandma!”

I went back to the funeral house and drank some millet beer under a crescent moon and a skyful of stars before heading home and leaving the crowd to its all-night vigil. After three days the family elders would meet to decide how and when the funeral ceremonies would take place.

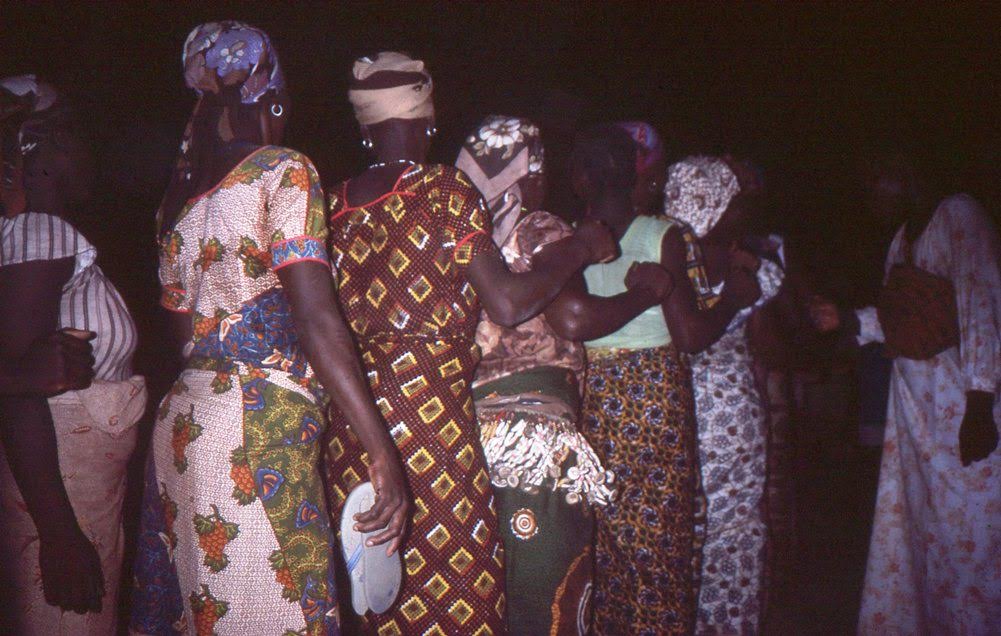

In a farming economy, it makes sense to wait until the off season to hold the funeral, when people have more time. Grandma’s funeral was held months later. The family fed multitudes. There was all-night dancing to the beat of two-tone flutes and “talking” drums. The dancers shuffled in a circle for hours, sustained by kola nuts and millet beer, falling into a kind of trance. The next morning they returned to their homes, joyful, radiant, as if huge weights had been lifted from their shoulders. And perhaps they had.

Karen Story is a writer who lives in Kirkland, Washington, where she

volunteers with hospice and attends Death Cafes.